Sharing the Secrets to "Creative Chaos"

By Julianne Mattera

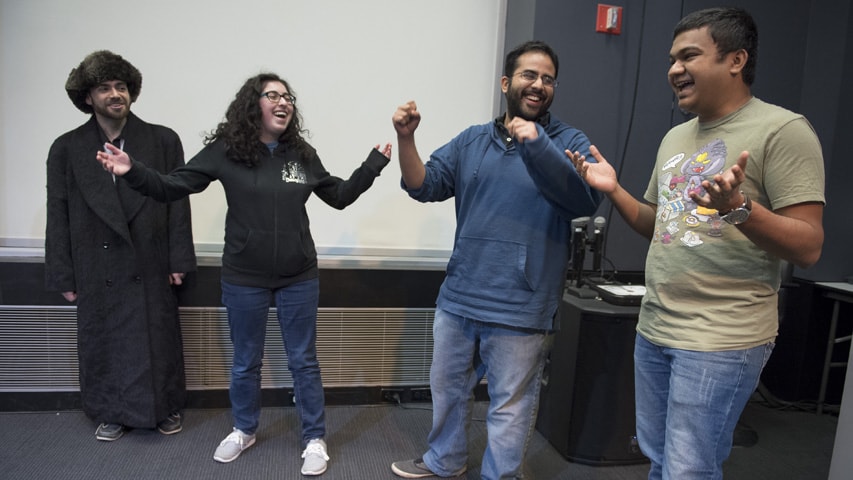

ETC students pictured from left are Jacob Rosenbloom, Brynn Gelerman, Jibran Khan and Pradnesh Patil during a recent improvisational class.

When diverse designers, artists and producers at Carnegie Mellon University's Entertainment Technology Center (ETC) work as a team to harness their skills, the frantic churn pushes innovative projects to new heights.

So it is no surprise that "Creative Chaos" is the title and focus of a new book from the ETC Press on best practices in teaching creative collaboration to the interdisciplinary groups in its interactive entertainment graduate program. Co-authored by ETC Director Drew Davidson and others, the book provides an overview of the ETC's work to foster an inclusive environment, welcoming constructive conflict in discussions and diversity in students' disciplines, worldviews, ethnicity and gender.

The ETC was founded in 1998 as a joint venture between the School of Computer Science and the College of Fine Arts. Most incoming students mirror that disciplinary mix. Now part of CMU's Integrative Design, Arts and Technology (IDeATe) Network, roughly 40 percent of first-year students in the ETC have technical backgrounds, such as computer science and engineering, and another 40 percent have artistic backgrounds, like graphics or visual effects, and the remaining 20 percent coming from a variety of areas (e.g. theater, creative writing, industrial design, business, audio, music, communications, etc.).

In the program, students collaborate on semester-long projects developing games, augmented reality, robotics, animation, mobile devices and location-based installations.

For Laurie Weingart, senior associate dean in the Tepper School of Business, the program was the perfect setting to study small group innovation among interdisciplinary teams. Between 2008 and 2011, Weingart and two doctoral students studied 60 ETC project teams to explore whether or not, and to what degree, more disciplinary diverse teams created more innovative work.

The study, which led to the book, found that "teams with more expertise diversity had more conflict about tasks in the form of disagreements and debates," but those disagreements ultimately led to final products that were "more innovative, useful, usable and desirable."

Specifically, Davidson said constructive conflicts — arguments that facilitate problem solving — become the "creative sparks."

"That's where the idea of creative chaos came about," Davidson said. "As you're working on these projects together, you're bound to have conflict because you're working with clients, faculty and people from different backgrounds. ... If you manage that known conflict well, it can be constructive and additive and you end up doing better work."

Weingart said that in order to be successful the group needs to work in an environment that supports constructive criticism and debate.

"The ETC is a perfect example of a living laboratory. They're using innovative processes to develop an innovative program to teach people how to drive innovation." — Laurie Weingart

"The ETC has that culture," Weingart said, noting that "Creative Chaos" encapsulates it in an effort to teach other groups and organizations how to imbue and support that culture.

Through further analysis of the data, researchers found that gender diversity contributes to more innovations since mixed gender teams often have a better exchange of ideas. Also, while teammates appear to work well together when they have some familiarity, it can be detrimental if they have too much familiarity.

Now, researchers are collecting a second data set that could bolster the study's original findings or lead in a new direction.

"The ETC is a perfect example of a living laboratory. They're using innovative processes to develop an innovative program to teach people how to drive innovation," Weingart said. "It's a really rich place to further our knowledge."

Building Creative Collaboration

One of the main ways the ETC teaches creative collaboration is through an improvisational acting course that students take in their first semester.

Brenda Bakker Harger, an associate teaching professor at the ETC, calls improv a "pure form of creative collaboration" in which improvisers generate ideas with their minds, bodies and by working off of each other.

"Only when you understand what it takes to be creative at that level can you start throwing elements like technology in the mix to further realize those ideas," Harger said.

Students in Harger's class learn to commit to the idea of "yes, and" — the notion of being open to new ideas and building upon them. In addition, Harger said successful improvisers must be comfortable with risk-taking and focusing on the project at hand (or narrative, in improv's case) instead of their egos.

"It doesn't matter if you're a great artist, a great programmer or a great producer, your skills are irrelevant by themselves," Harger said. "They only count when they are put together with the others on a lateral basis."

That culture of collaboration has stayed with many ETC alumni who now work at Schell Games, a Pittsburgh game design and development company founded by ETC instructor and CMU alumnus Jesse Schell.

Roughly 60 percent of the Pittsburgh company's design department graduated from the ETC, said Harley Baldwin, the company's vice president of design. When she started at the company three years ago, she found many people who saw collaboration as a core value in game development. That was a pleasant surprise for Baldwin who, at previous jobs, had taught teams how to work well together.

Baldwin said she is always happy to see ETC alumni while recruiting. In addition to their experience and exposure to the ETC's challenging curriculum, she knows that they have an understanding of the benefits of collaboration.

"Very often they can provide a linchpin for a team that really helps the whole team gel around a concept or an idea," Baldwin said.

Like Baldwin, Sabrina Culyba, a principal game designer at Schell Games, said the students graduating from the program are prepared to be leaders who "roll with the team" and help it move toward its goals, whether that be solving a problem or creating something new.

With that training, Culyba said ETC alumni have landed in nearly every company in the entertainment space.

Neil Druckmann, creative director for the video game developer Naughty Dog, said he's used the ETC's best practices throughout his career, which has included co-creating award-winning games like "Unchartered 4: A Thief's End," "The Last of Us" and the upcoming "The Last of Us Part II."

When Druckmann came to the ETC, he said he was quickly humbled by the fact he couldn't operate alone, and he learned to work with teammates' strengths and weaknesses.

In Schell's game design course, Druckmann recalled Schell pushing designers to listen during the creative process. Schell taught his students that even feedback they disagreed with would contain some truth, and, instead of arguing, it is best to listen and find that truth.

"It's not about having such a defined, specific vision where people find it suffocating," Druckmann said. "It's about finding the core truths of what this game is about and then letting people flourish and interpret and collaborate within that so they feel ownership of it.

"From 'The Last of Us' to 'Unchartered' and now to the sequel of 'The Last of Us,' when you're surrounded by talent, you want to make sure you leverage that talent," Druckmann said. "And that has stuck with me from the ETC."