|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|||

|

Carnegie Mellon joins battle for affirmative action during the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. celebration �

At Carnegie Mellon's Martin Luther King Day celebration, held five days after Bush's announcement, President Jared L. Cohon announced that Carnegie Mellon would file a friend-of-the-court brief in favor of the University of Michigan's position that race can be one of many factors considered in admissions. He did so because "the stakes in the Michigan case are so high, and diversity is so important to our university." In his Jan. 15 remarks, Bush described the University of Michigan's policies as a "quota system that unfairly rewards or penalizes prospective students, based solely on their race." The university contends that it doesn't use quotas. Each application is reviewed individually, academic qualifications carry the most weight and there are no set-asides, university officials say. However, undergraduate applicants who are underrepresented minorities can earn 20 points on a 150-point selection index. The Michigan case has attracted educators' attention nationwide because many universities use similar selection systems that could be affected by the Supreme Court ruling on the case. After Carnegie Mellon's admissions committee identifies all academically talented students, it considers how each will contribute to the campus mix, Cohon said in his "State of Diversity at Carnegie Mellon" address, Jan. 20. "Affirmative action does not mean lowering our standards, and it does not require sacrificing quality," Cohon said. "Rather, affirmative action is essential to making Carnegie Mellon a diverse university, which is crucial for making it the best university that it can be." Thirty-eight colleges and universities across the U.S. joined Carnegie Mellon in its filing, Feb. 18. They include Johns Hopkins, Marquette, New York and Syracuse universities. Cohon's speech was the first in a series of campus events celebrating the slain civil rights leader. At a panel discussion on King's six steps for nonviolent social change, Esther Bush, president and CEO of the Urban League of Pittsburgh, said she was discouraged and embarrassed by the country's current direction on economic and racial issues and by the insensitive timing of President Bush's announcement. But other hard-won changes are encouraging. She noted that four African-Americans have attained elected office in Allegheny County government since its restructuring a few years ago; in 113 previous years, no African-Americans achieved that. "It's going to take every single last one of us to try to move our country forward because there are going to be too many, in too many powerful positions, that are going to keep us down," she said. Joe Trotter, head of Carnegie Mellon's History Department and director of its Center for Africanamerican Urban Studies and the Economy, said the context for the struggle for racial justice has changed. International pressure to reform has abated since the Cold War, when the Soviet Union could keep civil rights in the forefront by accusing the United States of being an unjust nation. "The civil rights movement certainly benefited from the tension created by the Cold War," Trotter said. Another complicating factor is that the country is no longer "bipolar," black and white, but multifaceted, he said. —Ruth Hammond You can fool some of the computers... �

Blum's group created a number of puzzles called CAPTCHAS (rhymes with Gotcha!), which stands loosely for Completely Automated Public Test to tell Humans and Computers Apart. It's based on the Turing test, which suggests that you can call a computer intelligent when it can fool some of the people some of the time into thinking it's human. The CAPTCHA determines whether the "person" signing up for e-mail is a person or an automated program. A CAPTCHA called Gimpy generates type on a busy background. Humans can make out the words and type them in, but computers are clueless. The test sorts out the human and computer customers. Blum's group has capitalized on the computer's inability to read twisted type and make other easy human judgments. Of course, a team at the University of California at Berkeley cracked the Yahoo Gimby program. Blum thinks that's fine because it means someone will build a better CAPTCHA. Engineering plus � Carnegie Mellon will inaugurate a five-year program leading to a B.S. in engineering and an M.B.A. from the business school starting this fall. The program will include three internships in engineering and business. Students attack the castle question � � What would you do if you had 250 castles and hundreds of assorted churches, estates and other historical sites falling into disrepair? The Piedmont region of Italy, located in the northwest bordering France and Switzerland, boasts such riches.

These planners have visions of museums, conference and community centers, restaurants and performing arts centers in some of these historic buildings. The Polytechnic Institute will concentrate on the restorations. Fitzcarraldo will explore business opportunities. Bologna and Carnegie Mellon will provide management training for future occupants. The Master of Arts Management Program, directed by Dan J. Martin, is offered by the Heinz School and the College of Fine Arts. Gailliot Center advises the Congress � Carnegie Mellon trustee and three-time graduate Henry J. Gailliot has committed $5 million to the former Center for the Study of Public Policy. Now known as the Gailliot Center for Public Policy in the Graduate School of Industrial Administration, the center serves as an international economic policy adviser to the Joint Economic Committee of the U.S. Congress. Center director Adam Lerrick and chair Allan H. Meltzer are international economic policy advisers to Tom DeLay (R-Texas), majority leader of the House of Representatives. The center is recognized as an authority on international financial institutions, global economic policy, sovereign debt restructuring and development aid. "Everyone involved with the center maintains a common belief: markets provide better answers than regulation or command and controls," says Gailliot (IM'64), retired senior executive of Federated Investors Inc. Tartan declares independence ��

Johnson attributed cuts to the newspaper budget to a growing number of student organizations, growth of the Activities Board and "animosity between the JFC and The Tartan. They didn't find our coverage to be very gratifying," says Johnson. "We didn't feel that there ought to be funding influencing the stories we covered. This independence also frees us to grow into more than a student organization." See www.thetartan.org. Called to military duty ��

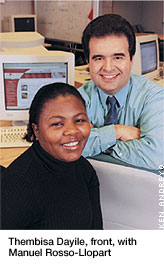

But the country needed Rush's skills before he could put the last bit of polish on them. Last September he got a call alerting him that he would be mobilized for a year or perhaps two, starting Oct. 30, in support of the anti-terrorism effort, Operation Noble Eagle. Rush's response: "That's great!" And to himself: "OK, where are the sedatives?" In July 2001, Rush, then a network manager for the National Guard in Little Rock, Ark., won a National Science Foundation Scholarship for Service to come to Carnegie Mellon. At the university, he supplemented his classroom learning with a work-study job at the CERT Coordination Center, which guards Internet security. Rush was touched by how sympathetic and supportive his professors and classmates were when he explained why he had to leave mid-semester. Some were taken aback, never having known anyone who was called to duty before. Rush hopes to finish his master's through distance learning from wherever he's stationed.—Ruth Hammond Closing the gender gap in computer science in South Africa �� When nine women who had just earned master's degrees at Carnegie Mellon flew back to their native South Africa, Dec. 9, they knew what jobs awaited them. They would join 11 other Carnegie Mellon alumnae at the Software Evaluation Center, a new government agency in South Africa's Department of Communications. There, for the next two years, they will test software the government purchases to make sure it performs as expected and advise government agencies on the best software to buy.

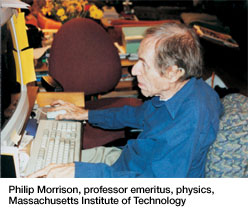

The international program's sponsors want to put South Africa in the forefront of software innovation, at the same time narrowing gender and racial gaps in computer science. In South Africa, only a third of computer science graduates are women. "That's why they've taken us from South Africa to here: to break the gender barrier," said Tlou Francina Mashao at a ceremony, Dec. 6, where she and her classmates received master of science in information technology degrees, with an emphasis in software engineering. Many girls who like computer science are discouraged by comments that women can't make it in the field, Mashao says, but she resisted such messages. "I told myself, 'If some of those guys have made it, I can make it.'" Dayile credits her interest in computer science to her family position. She is an only girl who often played with her four brothers. When the boys smashed their toys to reassemble them or built cars of wire, she paid attention and developed problem-solving skills, she says. South African women who do go into computer science are disproportionately white. Of women graduating in computer science in 1998, 69 percent were white and 16 percent black. The population is 11 percent white and 77 percent black. Vodacom Foundation, the program's primary funder, chose to sponsor female graduates of black universities for advanced training. The African cellular communications company's foundation sent three groups of women with undergraduate degrees in math or computer science to Carnegie Mellon. The last of the groups arrived in January. The women spend the first year of the program at the Institute of Software and Satellite Applications at Houwteq Learning Centre in Cape Town, taking distance-learning courses from Carnegie Mellon. That year prepares them to fit in at the Pittsburgh campus, where they study with other master's candidates for two more semesters. The Department of Communications gives each student her own laptop—for many the first computer they've owned. Before the first group returned home in August 2001, Manuel A. Rosso-Llopart, who runs Carnegie Mellon's South African program, recommended that government officials create jobs for the graduates. "These are going to be the most powerful software engineering women you have," he told them. The Software Evaluation Center sprang from his proposal. "It's nice to see something you write on a piece of paper come to life," says Rosso-Llopart (CS'92), a senior lecturer in the Institute for Software Research International (ISRI). He credits two Carnegie Mellon faculty members with creating the South African collaborative program: James E. Tomayko (HS'71), ISRI director, and Paul S. Goodman, the Richard M. Cyert professor at the business school and director of the Institute for Strategic Development. In Pittsburgh, Dayile says she was exposed to American friendliness, the high cost of living, Daylight Saving Time, unfamiliar food, idiomatic use of English and the variety of ways Americans and other international students approach software development. But there was one thing she didn't want to experience. "I hope the snow won't come while I'm here," she said. The day before her graduation, Pittsburgh got 4.8 inches of snow. It was one of the stories she took home with her.—Ruth Hammond Falconi succeeds Bolton as CFO �� Stefano Falconi became vice president for administration and chief financial officer at Carnegie Mellon, Jan. 1. He earned an M.B.A. from Harvard and a J.D. from the University of Padua in his native Italy. He previously served as director of finance at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and director of cost analysis at Harvard. Falconi succeeds Jeffrey Bolton, who has joined the Mayo Foundation of Rochester, Minn., as chief financial officer. � Philip Morrison: From A-bombs to burnt doughnuts �� "One nuclear war is plenty," says Philip Morrison, who worked on the Manhattan Project during World War II. He conducted uranium experiments that led to creation of the atom bomb. But the killing power of the bomb deeply disturbed him. After the war he turned to theoretical questions about the nature of the universe.

Now a professor emeritus of physics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology living in Cambridge, Mass., Morrison has enjoyed a long career as a theoretical physicist and science educator. He identified, and Nature published as a conjecture, his and colleague Giuseppe Cocconi's identification of the 21 cm wavelength of neutral atomic hydrogen as the best place to look for transmissions from intelligent extraterrestrial life. He co-authored "Powers of Ten: About the Relative Size of Things in the Universe," which uses pictures ranging from galactic clusters to the interior of a carbon atom. He reviewed books for Scientific American for 30 years and, in the 1980s hosted a television series, "Ring of Truth," that educated the public about science. On one program, he made a bonfire of dried-out doughnuts and compared the energy output to the work put out in a day by cyclists in the Tour de France. Since the series is still used in science education, Morrison sometimes has kids come up to him and inquire, "Hey, are you the guy who burned up the doughnuts?" Among his friends were visionaries of the 20th century: He lunched with Albert Einstein, compared notes with Niels Bohr, and worked with Enrico Fermi. Morrison, who grew up in Wilkinsburg, Pa., contracted polio as a child, and his father, worried about the housebound boy, bought him a crystal radio set. Later, Morrison built his own radio, volunteered at a radio station and earned a broadcasting license at the age of 12. By high school, he says, "I was a serious radio enthusiast." During the height of the Depression, he entered Carnegie Tech on a scholarship, determined to become a radio engineer. His choice of majors was not practical: "Nobody had a job...the issue of getting a job was moot. Might as well do what you liked," he explains. Living at home and commuting to campus by streetcar, Morrison discovered in his first semester that physicists asked more questions than engineers. He changed his major to physics. At Carnegie Tech, Morrison first encountered Einstein. In the winter of 1933 Morrison learned that the legendary physicist would talk to the American Association for the Advancement of Science on campus. The talk was open only to AAAS members. Morrison's friends in the Drama Department unlocked the theater and let him and several other eager students sneak in. They perched on scaffolding above the stage and only managed to see the top of Einstein's head. He gave a proof of conservation of momentum using relativity and wrote the formulae on a blackboard. "We couldn't see the blackboard at all," says Morrison. "We couldn't hear very well. But we were there!" Morrison went on to study theoretical physics under J. Robert Oppenheimer at the University of California at Berkeley. After the war he taught physics at Cornell University. During this period, he visited Einstein in his home and enjoyed a real exchange of ideas. He then joined the faculty at MIT.

At MIT in 1961 he met and married his second wife, Phylis Singer, a woman whose talent for everything from bread making in the Amazon to growing brightly colored salt crystals, inspired him to see art and creativity as inherent in science. "She noticed the nuances," says Morrison of Phylis, who died in July 2002. "We worked together, we wrote together. She found everything in the world interesting."—Jennifer Margulis

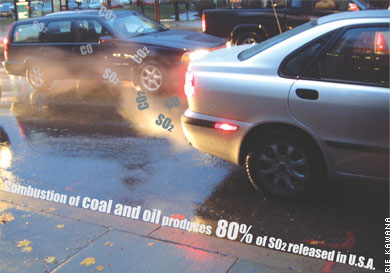

Sophomore addresses car pollution

�� Carbon nanotubes 101 �� Carbon nanotubes are 50,000 times "thinner than a human hair" and "strong as a diamond." Discovered in 1991 by Sumio Iijima of Japan, nanotubes, which are way too small to see, are basically a sheet of graphite rolled into a cylinder. You can even stuff them with stuff. Nanotubes have excellent thermal conductivity. They're chemically inert. They can hold electric current about 100 times higher than that used in metal wires. Some researchers have even thought of constructing a 70,000-kilometer-high nanotube space elevator for launching shuttles into space. At Carnegie Mellon, David Sholl, assistant professor, Chemical Engineering, and Karl Johnson of the University of Pittsburgh are focusing on nanotube membranes made from bundles of nanotubes that can filter gases quicker than current systems because they offer little friction. The researchers see the material as useful in industry for separating gases. They also see nanotubes' gas transport qualities as possibly applicable in separating hydrogen for use in fueling cars. "Properly sized and assembled nanotubes could separate gases with lower power requirements than current methods in power plant exhaust systems and fuel-cells for next-generation cars," says Sholl. West Coast campus expands �� Carnegie Mellon has signed a 15-year lease on Buildings 23 and 24 on Shenandoah Plaza at Moffett Field, Calif. The university will renovate the buildings for its West Coast campus, which began offering a master's program in information technology last September for 56 students. The campus held a Founders' Day, Dec. 10, to honor some 20 Silicon Valley leaders and others who together contributed $1 million to the campus. Qatar extends offer �� The tiny Persian Gulf state of Qatar has invited Carnegie Mellon to conduct its undergraduate programs in business and computer science in its 350-acre Education City. University Attorney Mary Jo Dively told the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review that the school views this "as a tremendous advantage for cross-cultural and educational exchange." Cornell operates a medical school and Virginia Commonwealth, a fashion and interior design program, in Education City. Carnegie Mellon administrators and faculty are evaluating the offer. Meanwhile, in Singapore �� Carnegie Mellon has forged a relationship with the two-year-old Singapore Management University to design and implement undergraduate business courses for its School of Information Systems. The school will open with 50 to 100 students in August. Singapore and Carnegie Mellon expect to explore joint student exchange programs, executive education and other initiatives. � Winning waste Carnegie Mellon took second place in two categories—pounds collected (286,000) and pounds per student (48.22) in the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection "Rush to Recycle Challenge," Oct. 7 to Nov. 30. � Programmers get definitive textbook

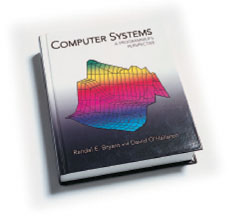

The book explains the concepts underlying all computer systems from a programmer's perspective. Schools adopting the text for first-time computer systems novices to hardcore programmers include Rice, Rensselaer, Northwestern, Middlebury, Minnesota, Rochester, Portland State, Oklahoma and Rocky Mountain. For more, see csapp.cs.cmu.edu. The financials �

The Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center and its sister centers at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and University of California, San Diego, were awarded $35 million to create the technological infrastructure for TeraGrid, a dedicated research network that will transmit data at 30 gigabits per second. That's 500,000 faster than a typical Internet dial-up (fast enough to download 750 copies of Shakespeare's complete works every second). The National Science Foundation has given a $9 million, five-year grant to Carnegie Mellon computer scientists and Pitt and MIT biological chemists and others to advance the field of computational biolinguistics. The research will study the sequences in amino acids in proteins to understand their structure, dynamics and function. The goal is to develop drugs to fight degenerative diseases, some of which are caused by defective triggers for shape and interaction in proteins. The General Motors Collaboration Laboratory at Carnegie Mellon will receive $8 million over five years to continue "smart car" research. The aim is to make a car that is more aware of driver needs and preferences, as well as road and weather conditions, and other information from the Internet. The vehicle will modify its behavior accordingly. It would also respond to the driver's gestural commands. The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation has awarded Carnegie Mellon a $1.9 million grant to develop free Web-based courses in formal logic, causal reasoning, statistical data, introductory microeconomics and introductory statistics. The National Science Foundation has approved a three-year $2.1 million grant to Carnegie Mellon to support the Virtual Agora Project, an effort to determine how information technology can support electronic democracy in which citizens can use the Internet to learn about, deliberate and act upon community issues. The Department of Engineering and Public Policy received a $1.1 million grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation to study ways to design safer airline, mail and other systems so they are not used as weapons against the nation. Science for dummies �

That's where journalists like National Public Radio science writer David Kestenbaum come in, trying to explain concepts like string theory in simple enough terms that those who profess no interest in science can understand them. Kestenbaum, who has a Ph.D. in physics from Harvard University, spoke at a Physics Colloquium in Wean Hall, Oct. 21. "You know a lot of amazing facts," he told his audience. "You know, for instance, that there's a storm of neutrinos going through this room. You know that in an electric power line the electrons don't go slowly down. They go down and then back, and then down and then back." And if the scientists could only explain such concepts properly, they could become the life of the party and irresistible to potential mates, he promises.

"People get stuck in this mode where they just don't speak English," Kestenbaum says. Yet the potential for engaging radio is there. "Every discovery has people behind it and characters and stories," he says. It also has suspense. Radio reporters try to incorporate that suspense in their stories, creating "driveway moments," when the commuter has arrived home but sits in the car long enough to hear the end of the story.—Ruth Hammond Long-time university volunteer Mac Connan dies �

� An emeritus life trustee of Carnegie Mellon, "Mac," as everyone knew him, was president of Connan Industrial Properties, a real estate firm. A member of the Class of 1939, he attended Carnegie Tech at a time when faculty routinely helped needy students with money from their own pockets. That, and the good food coming out of the Home Economics Department, often kept him enrolled, Mr. Connan said. � He worked on the Pennsylvania Turnpike New Stanton viaduct after graduation, started Pittsburgh Plastics in his hometown of New Kensington and served as a Naval gunnery officer during World War II. After the war, he moved to New York, starting a new plastics company. He later worked in aluminum processing and real estate. � Though a management-engineering graduate, he took up oil painting in his later years, traveling annually to New Mexico to capture the distinctive landscape there. He frequently showed his work and presented a retrospective of his paintings at the University Gallery during Homecoming last fall. � A founder of the Andrew Carnegie Society, the university's primary donor club, Mr. Connan helped a series of Carnegie Mellon presidents in their fund-raising efforts. The Andrew Carnegie Society had selected Mac and his wife, Gloria, an honorary alumna, to receive this year's Recognition Award for some 60 years of service to the university. At its annual dinner, April 5, Mr. Connan was honored posthumously. � The Connans were part of the founding committee of the Academy for Lifelong Learning on campus, an immensely successful continuing education program for seniors. Besides serving as a university trustee for 35 years, Mr. Connan had served both as president of the Carnegie Mellon Alumni Association and the Andrew Carnegie Society. The couple lived in Pittsburgh and Palm Beach, Fla. Services took place at Rodef Shalom Temple. A campus memorial is planned for 12:15-1:30 p.m., Monday, May 19, in the Connan Room, University Center. � Besides his wife, he is survived by his son Andrew and Andrew's wife, Roxanne; daughter Diana Connan Forgy (HS'72) and her husband, Charles Forgy (S'79); son Frederic; and four grandsons. � Memorial donations may be sent to the Maxwell H. and Gloria Connan Scholarship Fund, Development Office, Carnegie Mellon University, 5000 Forbes Ave., Pittsburgh, Pa. 15213.—Ann Curran Rob Marshall wows with "Chicago" � Back in 1981, Rob Marshall kicked up his heels in the title role of a rollicking, buzzin' original musical called "Rachinoff," directed by Drama School head Mel Shapiro. It told the story of a classical composer who discovered rock 'n' roll several centuries before Elvis. It was almost too big and lively for the intimate Kresge Theater in the College of Fine Arts. Word was that musical theater major Marshall was losing 10 pounds a week in the performance, easily believable with the energy he expended in the show.

In the final tally, "Chicago" won six Academy Awards, including Best Picture of the year; three Golden Globes for best musical, best actor (Richard Gere) and best actress (Renee Zellweger, in photos with Marshall); Broadcast Film Critics Association Critics Choice Awards, best supporting actress (Catherine Zeta-Jones) and best supporting ensemble; Bafta, best supporting actress (Zeta-Jones) and sound. Marshall didn't start at the top directing "Chicago" for Miramax Studios but has earned multiple nominations or awards for almost every show he has choreographed or directed, including the Broadway productions of "Cabaret," "Damn Yankees," "Kiss of the Spider Woman" and "Company."

Film Critic Ed Blank of the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review talked to some of Marshall's mentors. Shapiro (A'61) told Blank, "Whatever information you gave him, he just flew with it. If you showed him a spoke, he invented the wheel around it." Shapiro found "Chicago" "the most mature" of Marshall's works.

�

�

�

� > Back to the top > Back to Carnegie Mellon Magazine Home |

|||

|

Carnegie Mellon Home |

||||

On Jan. 15, on what would have been Martin Luther King's 79th birthday, President George W. Bush announced that his administration would file a brief with the U.S. Supreme Court arguing that affirmative action in university admissions is unconstitutional. The court is considering a lawsuit brought by two white plaintiffs who claim they were unfairly denied admission to the University of Michigan because of preference given to African-Americans.

On Jan. 15, on what would have been Martin Luther King's 79th birthday, President George W. Bush announced that his administration would file a brief with the U.S. Supreme Court arguing that affirmative action in university admissions is unconstitutional. The court is considering a lawsuit brought by two white plaintiffs who claim they were unfairly denied admission to the University of Michigan because of preference given to African-Americans.

To save the sites and make them integral to the area with the help and participation of local communities, Carnegie Mellon's Master of Arts Management Program has entered into an agreement with the University of Bologna's Department of Economics and Management, the Polytechnic Institute of Turin's Second Architecture Faculty and the Fitzcarraldo Foundation of Turin.

To save the sites and make them integral to the area with the help and participation of local communities, Carnegie Mellon's Master of Arts Management Program has entered into an agreement with the University of Bologna's Department of Economics and Management, the Polytechnic Institute of Turin's Second Architecture Faculty and the Fitzcarraldo Foundation of Turin.

The Tartan student newspaper has severed its financial ties to the university. Rejecting an allocation of $16,000—less than 15 percent of The Tartan budget—from the Joint Funding Committee, the student-operated newspaper plans to raise its entire budget of about $120,000 from advertising, reports Editor-in-Chief Andrew Johnson, right, a senior in electrical and computer engineering.

The Tartan student newspaper has severed its financial ties to the university. Rejecting an allocation of $16,000—less than 15 percent of The Tartan budget—from the Joint Funding Committee, the student-operated newspaper plans to raise its entire budget of about $120,000 from advertising, reports Editor-in-Chief Andrew Johnson, right, a senior in electrical and computer engineering.

National Guard Capt. Chris Rush was down to his last semester at the Heinz School, pursuing a master of science in information technology with a specialization in information security and assurance. He had already landed a job as an information security specialist with the Federal Aviation Administration. He and his wife, Kathy, had put a deposit down on an apartment in Washington, D.C.

National Guard Capt. Chris Rush was down to his last semester at the Heinz School, pursuing a master of science in information technology with a specialization in information security and assurance. He had already landed a job as an information security specialist with the Federal Aviation Administration. He and his wife, Kathy, had put a deposit down on an apartment in Washington, D.C.

One of the graduates, Thembisa P. Dayile, says it's important to show the department and the whole of South Africa what they've learned at Carnegie Mellon "so the next generation will be interested in sending others to come and study here."

One of the graduates, Thembisa P. Dayile, says it's important to show the department and the whole of South Africa what they've learned at Carnegie Mellon "so the next generation will be interested in sending others to come and study here."

But his past remained vivid. And in the late 1970s, Morrison (S'36) formed the Boston Study Group of scientists and professionals committed to averting nuclear war and reducing military spending. Together they wrote "The Price of Defense: A New Strategy for Military Spending" in 1979. Adopted by The Nation as a gift to new subscribers, the book became a cult classic of the left and a leading text in the argument against nuclear proliferation.

But his past remained vivid. And in the late 1970s, Morrison (S'36) formed the Boston Study Group of scientists and professionals committed to averting nuclear war and reducing military spending. Together they wrote "The Price of Defense: A New Strategy for Military Spending" in 1979. Adopted by The Nation as a gift to new subscribers, the book became a cult classic of the left and a leading text in the argument against nuclear proliferation.

The book "Computer Systems: A Programmer's Perspective," published by Prentice Hall, went into 18 schools for use last fall. Authors are Randy Bryant, head, Computer Science Department, and Dave O'Hallaron, associate professor of computer science and electrical engineering.

The book "Computer Systems: A Programmer's Perspective," published by Prentice Hall, went into 18 schools for use last fall. Authors are Randy Bryant, head, Computer Science Department, and Dave O'Hallaron, associate professor of computer science and electrical engineering.

Sometimes it's hard for researchers to convey all the exciting things going on in science without making their listeners' eyes glaze over.

Sometimes it's hard for researchers to convey all the exciting things going on in science without making their listeners' eyes glaze over.

�

� Two decades after graduating, Marshall (A'82) has rocked the film world in his big-screen film debut directing and choreographing the musical "

Two decades after graduating, Marshall (A'82) has rocked the film world in his big-screen film debut directing and choreographing the musical "