|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Combat vehicle planned

Carnegie Mellon's National Robotics Engineering Consortium and Boeing Integrated Defense Systems in St. Louis will receive $5.5 million over 18 months to construct the first all-terrain, unmanned ground combat vehicle. It will be named the Spinner. With no humans aboard the vehicle, engineers can ignore amenities, but the final product will climb four-foot steps, stay on duty for 14 days without refueling and hit the war scene faster than a tank. The vehicle is expected to operate even if it's turned over. It can also stack itself on top of similar vehicles.

� Dogs have their day The powers behind the CMPack'02 dogs were Manuela Veloso, associate professor, Computer Science; doctoral students Scott Lenser, Ashley Stroupe, Maayan Roth and Doug Vail; and senior Sonia Chernova.

Some 29 countries, 188 teams and 1,004 people participated in the competition. The aim of the games is to develop a team of robots by 2050 that can defeat the human world champions in soccer. RoboCup 2003 will take place, July 2-11, in Padova, Italy. Carnegie Mellon will host the RoboCup First American Open, April 30-May 4,

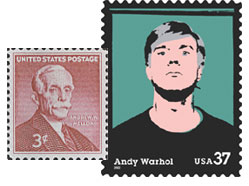

� Andys stamp out a reputation The atypical guests mobbing the event included philatelists in search of first-day covers, blocks and panes of stamps and postmarks.

Printed in shades of teal, gray, pink and black, the stamp is based appropriately on Andy Warhol's "Self-Portrait" (1964), which originated with a photo-booth snapshot. The artist worked in silkscreen ink and synthetic polymer on canvas. The Postal Service printed some 61 million stamps, in a work designed by Richard Sheaff, commemorating the pop artist Warhol (1928-1987). The selvage or edge of the stamp sheets contains detail of a photograph taken by a Warhol factory hanger-on called Billy Name as well as Warhol's quotation: "If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There's nothing behind it." Pittsburgh Mayor Tom Murphy spoke at the event honoring the artist, born Andrew Warhola, son of Carpatho-Rusyn immigrants to Pittsburgh. You can shop for Warhol stamps at www.usps.com/shop.

Carnegie Mellon's other "Andys"—Andrew Carnegie, the founder, the King of Steel and philanthropist extraordinaire, and Andrew W. Mellon, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury and head of a dynasty of philanthropists—got pasted earlier. You can still pick up the 1960 Carnegie four-cent stamp, showing the founder in a library with a book, and the 1955 Mellon three-cent stamp for a dime. "They are common," says Michael Schreiber of Linn's Stamp News, www.linns.com. Warhol, of course, will cost you 37 cents. Inflation.—Ann Curran "Green Room" educates on recycling

Painted cream and a lush spring green with a lick of sunshine, the recycling station is "mostly educational," says Barbara Kviz, environmental coordinator, who set it up with the help of alumni Roger Wei (A'01) and Ayaka Uchida (A'01), who designed it, and recycling intern Alexis Hanczar. It opened officially on Earth Day, April 22. An overriding message in aquamarine on cream, painted around the upper wall, announces the motivation: "All things share the same breath—the beast, the tree, the man. • Knowing is not enough; we must apply. • Willing is not enough; we must do. • Trees are poems that earth writes upon the sky. • We are but one thread in the web of life." Around the space are containers for the obvious and less obvious recyclables: trash, glass, plastic, transparencies, CDs, cardboard, office paper, newspaper. You'll find a brief explanation about the Mobius—that arrow that chases its tail in a circle—which has become the universal symbol for recycling. There's also info on the waste people produce (4.4 pounds per day) and what can't be recycled—paper with food on it, wet paper, pizza boxes, tissues, etc. A couple of iMac computers trace recyclables in living color from waste to reusable products with a click of a mouse. For example, glass picked up at the University Center goes to A&K Glass in New Stanton, Pa. It's sorted by color—clear, brown, green, blue—and broken into cullet. Magnets, screens and a vacuum system remove metal, labels, plastic, rings and caps. The company then blends the cullet with silica sand, soda ash and limestone, melts it at 2700 F until molten and blows it to fit molds of new glass.

It's an education. One freshman—first day on campus—wanted to know if she could check her e-mail on the iMac. Well, it got her closer to the message anyway.—Ann Curran

� Libraries shelve one millionth volume

� At Homecoming, Oct. 5, President Jared L. Cohon accepted two books from Dame Gillian Wagner, trustee of Carnegie U.K. Trust, headquartered in the founder's hometown of Dunfermline, Scotland. The books marked acquisition of the University Libraries "millionth volume" and are a gift from the Carnegie family heirs. The two books, inscribed to the Andrew Carnegie family, are titled "Liber Scriptorum" (book of writers) published in 1893 and 1921. Originally part of Carnegie's personal library at Skibo Castle in Scotland, they contain the work and signatures of some 238 authors, including Carnegie, William Dean Howells and Mark Twain. The books will become part of the Fine and Rare Book Room at Hunt Library. Instrumental in bringing the gift to Carnegie Mellon were Trustee Lucian Caste (A'50) and his wife, Rita Ebner Caste (HA'90), and William Thomson, great-grandson of Carnegie and board chairman of the Carnegie U.K. Trust.

Last year, the libraries, under the direction of Gloriana St. Clair, reached their one millionth page of digitized archival matter available on the Internet. And, within five years, the libraries, in cooperation with institutions in India and China, expect to deliver some one million digitized books, available for reading at http://ul.cs.cmu.edu/.—Ann Curran

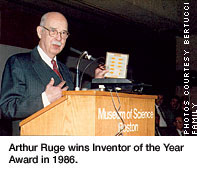

� Alumnus Arthur Ruge invented strain gauge used in many industries

�

But Ruge, who died April 3, 2000, wasn't the first to invent the strain gauge. That distinction went to Edward E. Simmons at California Institute of Technology, whose work was done two years earlier. Ruge initially didn't even enjoy complete rights on his invention, which were shared with his employer, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Unlike Simmons or MIT, Ruge understood the value of his invention. Simmons didn't grasp its importance until Ruge began commercialization of his strain gauge. Then Ruge learned of Simmons' work. MIT's patent committee handed its rights to Ruge, describing it as "interesting" but not seeing its potential. Ruge devoted much of his life to his invention, refining the technology and developing applications.

The Ruge strain gauge or SR-4 "was a deceptively simple invention composed of four thin tungsten filaments, similar to those used in light bulbs, glued together in the shape of a diamond," wrote The New York Times in Ruge's obituary. "When an electrical current is run across the wires, no voltage can be measured as long as they remain perfectly aligned. But if some force distributes the symmetry, and thus the resistance in the wires, the gauge puts out a voltage proportional to the force. For the first time...mankind now had a method [of weighing objects] that did not rely on balancing the force exerted by the object being weighed against some other weight or force," the Times reported. The invention became vital in World War II in the design of aircraft, gun barrels and other machinery. "The first signal received from the moon was a reading from a strain gauge on the leg of the lunar lander." James H. Garrett (E'82, '83, '86), director of Carnegie Mellon's Advanced Infrastructure Systems in the Institute for Complex Engineered Systems, says Ruge's strain gauge was a significant event in the evolution of engineering. "We are researching the use of sensors, including strain gauges and temperature sensors, in conjunction with...power sources, electronics and wireless technologies to eventually be able to continuously measure in situ parameters that most affect structures." Garrett's group wants to provide data that could be used to control maintenance costs, tweak future designs and, in some cases, such as bridges, increase the time available for use. "Among other things, AIS's research seeks to extend the reach and application of Ruge's art," Garrett says. Ruge received many awards over his lifetime, including the Carnegie Mellon Alumni Association Merit Award in 1959. His daughter, Claire Ruge Bertucci (MM'65), and son-in-law, John R. Bertucci (E'63, IA'65), and two granddaughters live in Lexington, Mass.

Ruge's work affected many disciplines including civil, mechanical and aeronautical engineering and most industries such as automotive and construction. It is difficult to imagine an aerospace industry without strain gauges. His legacy extends the ability of engineers and scientists to design systems to make the world work better.—Sam Blackburn IA'90 "Flowering Dogwood" � Old Glory � Charlie Moore remembered

Robert W. Wolff (A'60), who taught drama at Carnegie Tech from 1968-72, says, "I remember thinking in acting and directing class that this man could explain anything and make it seem simple and understandable—and even more important for actors-playable." Others remembered his cigarette holder, his "electrifying" performance in a Dostoevski adaptation, directed by grad student Mel Shapiro (A'61), who later headed the Drama Department. Such reminiscences prompted a group of Charlie Moore's former Carnegie Tech students and faculty who worked with him to establish the Charles Werner Moore Memorial Fund for student travel and a Moore pictorial archive. Leading the group were Rene Auberjonois (A'62) and wife Judith Mihalyi Auberjonois (A'65), Len Auerbach (A'66), Jamie Cromwell (A'64*), Jennifer Darling (A'65), Gil Dennis (A'65*), T. J. Escott (A'62), Ron Frazier (A'65), Dick Hughes (A'66), Steve Lemberg (A'66), Lilene Mansell (A'66), Caroline McWilliams (A'66), Tom Tarpey (A'65), Michael Tucker (A'66), Bruce Weitz (A'66) and faculty Ted Kazanoff, Lew Palter and wife Nan Palter.

Charlie Moore connected, and for many of his former students, that connections still exists.—Ann Curran.

� Lepper show runs at Warhol

Lepper (1906-1991) helped to set up the first degree program in industrial design in the U.S. at Carnegie Mellon, and many of his artworks capture his interest in industrial shapes and products. The exhibit emphasizes his work as muralist and sculptor with pieces from several collections, including Carnegie Mellon and the artist's estate. Some works have not been shown before. In Lepper's course called Individual and Social Analysis, taken by Warhol, he asked students to focus on important objects in their lives. Later, Warhol came up with his Campbell's Soup Can paintings, drawn from his childhood memory of meals at home. At least one scholar has tied those events together. Besides Warhol, Lepper's students include author and illustrator Leonard Kessler (A'49), painter and Warhol chum Philip Pearlstein (A'49, H'83), conceptual artist Mel Bochner (A'62) and editorial cartoonist Jimmy Margulies (A'73). Robert Lepper made a number of public works: sculpture for the 1964 World's Fair in New York and bas-relief industrial works at the main entrance to Carnegie Mellon's Graduate School of Industrial Administration. The show will exhibit models for a proposed 60-foot-tall, fire-breathing dragon, called "River Creature," which the artist felt captured Pittsburgh's industrial past, the humor requisite for any artist and the good nature of the city's people.

Matt Wrbican (A'81), assistant archivist for The Warhol, is curator of the Lepper show.

� Back-to-back wins for Brockenbrough While he crossed the finish line first at the U.S. National Long-Course Triathlon Championships in Muncie, he dropped to second place because of a four-minute penalty. But in Pittsburgh, he won the men's division the very next day. That event included a 1.5-kilometer swim, 40K bike race and 10K run.

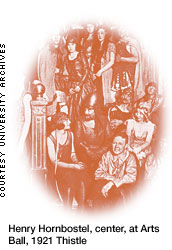

It's kind of genetic. His father, Roger Brockenbrough, won in his age group in Muncie and in the Hawaii Ironman Triathlon two years ago at 66. A mechanical engineer with Alcoa, John Brockenbrough lives in Murrysville, Pa., with his wife, Laura, and son Spencer. Henry Hornbostel shaped the campus

Unfortunately, Hornbostel didn't get his contract renewed in 1936. Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation has just published the first book on this flamboyant architect whose work is sprinkled around the nation and around Pittsburgh (Rodef Shalom, Soldiers' and Sailors' Memorial Hall, Pittsburgh City-County Building, Grant Building). It's "Henry Hornbostel: An Architect's Master Touch" by Walter C. Kidney and aims to "promote an awareness of his genius." Look for the H's in his buildings. He apparently left his initials—in large and obvious places—in the design of many of his works.—Ann Curran

�� Babies hear it all

Sigma 5 retires to computer museum Blowing our own horn

� David A. Dzombak, professor, Civil and Environmental Engineering, picked up the 2002 Professional Research Award from the Pennsylvania Water Environment Association, for work on municipal and industrial waste-water treatment. Alan M. Fletcher, head, School of Music, accepted the Paul Revere Award for Excellence in Musical Score Design for his composition "An American Song," performed in celebration of the bicentennial of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Jerry H. Griffin, professor, Mechanical Engineering, was named the William J. Brown professor of mechanical engineering. Brown's research in turbomachinery vibrations has modified the design of aircraft turbine engines, making them safer. Elizabeth W. Jones, head, Biological Sciences, received a $1 million grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. She was one of 20 professors from a pool of 84 nominated to receive the award in recognition of her work in enhancing undergraduate education. Priya Narasimhan, research scientist in the Institute for Software Research International, earned the IBM Faculty Partnership Award of $40,000 for her work on secure dependable Web services. Kathryn Shaw, economics professor, Graduate School of Industrial Administration, was awarded the Ford Distinguished Research Chair.

Sebastian Thrun, associate professor, Center for Automated Learning and Discovery, received a three-year appointment to the Finmeccanica chair, which honors junior faculty. Grace under pressure

� The brainchild of Reid G. Simmons, senior research computer scientist in Carnegie Mellon's Robotics Institute, and Alan C. Schultz, computer scientist at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C., the competition among robots was clearly led by the six-foot-tall, 300-pound Grace, who arrived at the conference center, boarded the elevator, registered, went to the auditorium and delivered a speech. "My chassis," Grace proclaimed boldly to the enthralled scientists, "is an iRobot B-21 base with two Pentia running Linux. I have a laser range finder, sonar and both stereo and monocular active heads for vision." The crowd of 300 ate it up and hoped for more. With a laptop head and a face that resembles Lara Croft, a character in Tomb Raider video games, Grace takes her name from Graduated Robot Attending Conference. Others involved in making Grace, besides Carnegie Mellon and the Naval Research lab, were Northwestern University, Swarthmore College and Metrica, which designed Grace's ability to interpret speech and gestures.

"See you next year in Acapulco," she murmured about the annual confab. It was clearly a 21st century Marilyn Monroe moment.

2002 rankings�

Rankings are based on peer assessment, graduation and retention rates, faculty resources, student selectivity, spending per student, graduate rate performance and alumni giving.

Business at third worldwide

� Myrna Rosen teaches ancient art of calligraphy with text appeal

�� As she describes the different uses for her writing tools, Rosen opens a small book that she bound and lettered herself. Made of heavy black card stock, the books' pages are covered in lines of text so intricate that at first glance they look like columns of filigree. The lines are a selection of popular titles, lines, verses from Shakespeare, bottom left, in as many colors and sizes as there are pens on the table.

You can probably recognize a calligrapher when you see one. Just as commercial painters wear paint-speckled boots, calligraphers bear a mark of their craft—an ink-stained ring finger. Today Rosen's fingers are smudged with black ink, traces of a project from one of the calligraphy classes she teaches in Carnegie Mellon's Design School. This fall, Rosen is teaching three courses. Her classes always have waiting lists. "Rosen offers her students a view of the world beyond the discipline of shaping letters. She offers a perspective into how calligraphers have been a part of history, culture and the arts," says Dan Boyarski, Design School head. "She is a humanist through and through, and she teaches with grace, passion and a sense of humor."

Rosen got her start in calligraphy by accident. As a gift, she received a calligraphy set, worked through the instruction booklet and lettered a few thank you notes to friends. She had no idea what she was getting into, although she admits that she was "hooked by the smell and glimmer of the wet ink and the gentle scratching rhythm of the pen on the paper. It's like looking through the wrong end of a funnel. You think calligraphy is such a small craft, but the more you know about it, the more you realize there is to know," says Rosen.

Known to Rosen and her peers as "The Guardian of the Alphabet," Bank quickly recognized Rosen's talent and made her his apprentice. "I was a sponge" for him, says Rosen, as she learned not only the beauty of letters in books and papers but also "the incising of letters in stone" and "the exciting world of paleography." "Rosen is very well respected within the calligraphic arts community for her teaching and personal artwork," says Anne Binder, president of the Association for the Calligraphic Arts. Rosen recently completed the exemplars for the association's "Calligraphy For the Classroom" program for Modern Romans. "Rosen has strength, character and darn good letterforms!" says Binder. She has taught at Carnegie Mellon for more than two decades. She also teaches at the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts. She's currently working with a painter on restoration of the benefactors' tablets in the Duquesne University chapel.

"Having survived the advent of the printing press, the typewriter, and the computer," says Rosen, "calligraphy is finding a place in the world of fine art." And she's helping to keep it alive.—Sara Weiner

�

�

� > Back to the top > Back to Carnegie Mellon Magazine Home |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Carnegie Mellon Home |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

It was inevitable. Andy Warhol (A'49), a quirky pop artist, filmmaker and illustrator who took his inspiration from supermarket shelves and the popular press, has wound up on a stamp. The U.S. Postal Service issued the big, splashy Andy on Aug. 9 in a party at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.

It was inevitable. Andy Warhol (A'49), a quirky pop artist, filmmaker and illustrator who took his inspiration from supermarket shelves and the popular press, has wound up on a stamp. The U.S. Postal Service issued the big, splashy Andy on Aug. 9 in a party at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.

Founder Andrew Carnegie meant well when he told his new Carnegie Technical Schools to use the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh down the street. But by 1937, school historian Arthur W. Tarbell noted the irony in the fact that the world's greatest founder of libraries had established a school with "one of the smallest and humblest libraries in the land."

Founder Andrew Carnegie meant well when he told his new Carnegie Technical Schools to use the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh down the street. But by 1937, school historian Arthur W. Tarbell noted the irony in the fact that the world's greatest founder of libraries had established a school with "one of the smallest and humblest libraries in the land."

According to The Boston Globe, the idea came to him in 1938: "The invention just popped into my mind, whole. I could see it clearly and knew that it would work." He made the device from wire and glue and said it was "a modest-looking instrument the size of a fingernail."

According to The Boston Globe, the idea came to him in 1938: "The invention just popped into my mind, whole. I could see it clearly and knew that it would work." He made the device from wire and glue and said it was "a modest-looking instrument the size of a fingernail."

It was Charlie Moore who told the male actors "that our first big paychecks should go into a wardrobe of wigs," Charles Oberdorf (A'63) recalled at a memorial for Charles Werner Moore at Brandeis University, where he had taught from 1965-88. Moore recommended the following wigs: "One in your own hair color, but long for Shakespeare...one bald wig with a horseshoe of your own hair color; one almost all gray but with some of your own color, and unless you've got naturally black hair, one black wig, for all the roles where that makes sense in terms of nationality."

It was Charlie Moore who told the male actors "that our first big paychecks should go into a wardrobe of wigs," Charles Oberdorf (A'63) recalled at a memorial for Charles Werner Moore at Brandeis University, where he had taught from 1965-88. Moore recommended the following wigs: "One in your own hair color, but long for Shakespeare...one bald wig with a horseshoe of your own hair color; one almost all gray but with some of your own color, and unless you've got naturally black hair, one black wig, for all the roles where that makes sense in terms of nationality."

But Lepper (A'27) said the then Andrew Warhola would turn in assignments that were "very good stuff." The Andy Warhol Museum is exploring the link between teacher and student in the exhibit "Robert Lepper, Artist & Teacher," which continues through Jan. 12.

But Lepper (A'27) said the then Andrew Warhola would turn in assignments that were "very good stuff." The Andy Warhol Museum is exploring the link between teacher and student in the exhibit "Robert Lepper, Artist & Teacher," which continues through Jan. 12.

Hornbostel became a member of the school's first faculty; introduced the Beaux Arts Ball during his year as Fine Arts dean, 1911-12 (the ball is a periodic costume party that frightens deans and dents the budgets); and encouraged the draftsmen working on the Gymnasium and making music with a tin wash tub, tin whistles and traditional instruments to come up with "Fight for the Glory of Carnegie." Robert W. Schmertz (A'21) wrote the words and music.

Hornbostel became a member of the school's first faculty; introduced the Beaux Arts Ball during his year as Fine Arts dean, 1911-12 (the ball is a periodic costume party that frightens deans and dents the budgets); and encouraged the draftsmen working on the Gymnasium and making music with a tin wash tub, tin whistles and traditional instruments to come up with "Fight for the Glory of Carnegie." Robert W. Schmertz (A'21) wrote the words and music.

It took five schools and a robotics company to get Grace, a robot and instant media darling, up and running at the annual meeting of the American Association for Artificial Intelligence, July 28 to Aug. 1, in Edmonton, Canada.

It took five schools and a robotics company to get Grace, a robot and instant media darling, up and running at the annual meeting of the American Association for Artificial Intelligence, July 28 to Aug. 1, in Edmonton, Canada.

Myrna Rosen unzips her leather tool case, and dozens of writing instruments spill onto her kitchen table. Rolling pens, brushes, reeds and slips of cardboard of various sizes are some of the tools that Rosen wields to create her calligraphic art.

Myrna Rosen unzips her leather tool case, and dozens of writing instruments spill onto her kitchen table. Rolling pens, brushes, reeds and slips of cardboard of various sizes are some of the tools that Rosen wields to create her calligraphic art.

In 1974 Rosen found another window into the calligraphic community through Arnold Bank, a long-time Carnegie Mellon fine arts professor with whom she studied until he passed away in 1986. "Arnold Bank is credited with sparking the calligraphy movement in America," says Rosen.

In 1974 Rosen found another window into the calligraphic community through Arnold Bank, a long-time Carnegie Mellon fine arts professor with whom she studied until he passed away in 1986. "Arnold Bank is credited with sparking the calligraphy movement in America," says Rosen.