|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

No house calls, just phone and web calls Telemedicine Pioneer Treats Patients Any Time, Anywhere Through WorldClinic, alumnus Daniel Carlin has rescued the medically needy from mid-ocean to mountaintop and tight spots in between. By Ruth Hammond

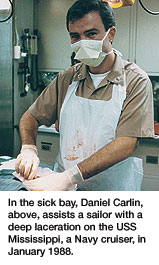

Because the USS Mississippi had no flight deck, the Navy helicopter summoned to transport the sailor to a hospital couldn't land. It had to hover above the deck, oscillating up and down in the same pattern as the ship riding the waves below. The helicopter crew dropped a line and pulled up "this poor sailor who's strapped in a cage," Carlin recalls. Any miscalculation about the wave pattern, and the helicopter and deck of the ship could meet in disaster. The sailor's life was saved, and so was Carlin's standing. That was just one episode in an eventful life. Carlin (S'81) went on to become a doctor who took risks, played for high stakes and stood at the center of dramas involving other imperiled sailors on isolated seas. The practice of emergency room medicine, where decisions made under duress have life-or-death consequences, would seem to offer plenty of excitement. But Carlin introduced other complications to his practice when he founded WorldClinic in 1998: distance, treating unseen patients, relying on the Internet and telephone for communications, becoming a trendsetter in a new field at a time when many investors have become disillusioned with Internet-based medicine. Like the helicopter that had to respond to the movements of the sea and ship below it in order to remain intact, Carlin has had to adjust to the waves and ebbs of enthusiasm for medical dot-coms to keep WorldClinic aloft.

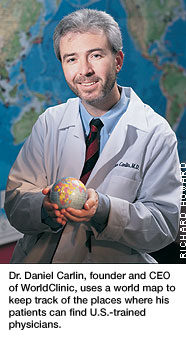

WorldClinic reaches out to workers, travelers abroad To find the best providers of U.S.-style medical care around the world, Carlin surveyed U.S. board-certified physicians, who recommended foreign-born medical school classmates or colleagues in their native countries. Relying on his research, Carlin has connected a man having a heart attack in a Beijing hotel room to a good cardiologist and referred a mother in Spain to a pediatric neurologist. WorldClinic covers medical expenses of up to $50,000 at foreign hospitals and offers medical evacuation through its partner, the Alabama-based MEDjet International. Originally affiliated with the New England Medical Center, WorldClinic moved to Lahey Clinic in 1999. The innovative program fit into Lahey's mission, says Karen Moyer, Lahey's director of business development. Lahey had already established programs in international health and executive health to meet the needs of the region's many workers in higher education and high technology who travel the world. The Boston area was a good market for a traveler's insurance that would not just evacuate someone in an emergency but try to keep clients out of the hospital through early intervention and oversee their care if they were hospitalized abroad. Carlin "provides a much more holistic solution, which is really what executives need," Moyer says. "They can't have diarrhea when they're going into a major negotiating meeting." Since it began, WorldClinic has served about 4,000 clients, with 1,200 presently enrolled, Carlin says. But the potential is much larger. A press release posted on WorldClinic's Website predicts further expansion into the "corporate executive and high net-worth individual markets, segments that comprise 2.8 million American expatriates, 10 million American international business travelers and 23 million American leisure travelers."

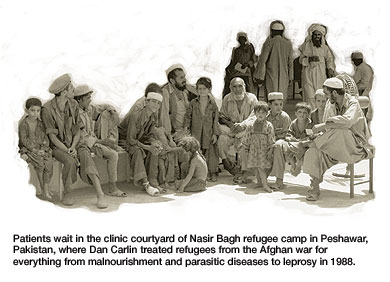

An impatient risk taker and compassionate volunteer The communication skills his father modeled are useful when Carlin discusses a child's genetic disease. "I have to speak in terms a mom and dad can understand and embrace. At the same time in the back of my mind is not only which chromosome this genetic mishap has occurred on and what the mismatch is and whatthe implications are and knowing the signs of it, but also the clinical side of it, how it's going to play out in the course of this person's life," he says. "So you have this very deep molecular science going on.... And at the same time, every single one of these things plays out in the life of a human being." After an absence of 16 years, Carlin came back to Pittsburgh in November to talk to a group of University of Pittsburgh Medical Center emergency room physicians about staffing WorldClinic's virtual emergency room. He walked around the Carnegie Mellon campus, soaking in the details of the new buildings, noticing even faculty artist Carol Kumata's ornamental brass curtains high on the facade of the Purnell Center for the Arts. In another media interview, Carlin described his life at Carnegie Mellon as arduous. It was harder than medical school, he reiterated in November. In what way? "To be perfectly honest, I had a really great social life here," he says. Carlin was active in his fraternity, Pi Kappa Alpha, and played soccer all four years, serving as captain his senior year. "I had all these other things at least as interesting as studying, and the tricky part was, on Friday or Saturday evening, you'd love to go out and raise hell with your friends, and you couldn't." He started out majoring in chemistry but took an interest in philosophy in his sophomore year and pursued a double major. In one class he'd learn about atoms and molecules and in the next discuss the arguments for and against the existence of God. But that wasn't enough for him. Asked why he's willing to take risks, he cites what he learned from the engineering class Systems Analysis and Design at Carnegie Mellon. He never actually took the class; his fraternity brothers did, and he got drawn into their assignments. "They had to solve engineering problems. I was so jealous of them because I thought, 'Wow, I'd love to do that,' and I often did. I often would not do what I was supposed to do" but instead joined his buddies in trying to figure out how to throw an egg off a building without breaking it or how to build a one-meter suspension bridge that could support a 10-kilogram load. "Those are things that I found absolutely fascinating." Looking at a problem and devising a solution "is clearly a Carnegie Mellon quality," he says. Other personal attributes diverted him from a conventional career path. "I'm an intensely curious person," he says. And "I'm terribly impatient: This is a character flaw my wife has pointed out many times. I have this thing where, gosh, wait a second, I see the future." His question is always, "How do we get there? Because I want it to happen tomorrow." Fortunately, he says, his wife, Lisa, shares his attitude that life isn't a deliberately safe exercise. Carlin met Lisa Salerno when both were involved in service to people on the opposite side of the spectrum from the "high net-worth individuals" WorldClinic targets. While aboard the USS Mississippi, Carlin read Somerset Maugham's novel "The Razor's Edge," about a man who travels the world on a spiritual quest. "It made me really think of the possibilities of my life and what I could do." On June 28, 1988, seven days after he was released from the service, Carlin was in Peshawar, Pakistan,serving refugees from the war in Afghanistan. He was there six months, and like other aid workers, became chronically ill with fever and dysentery. He was carrying only 149 pounds on his 6-foot-3 frame when he returned to the United States to gain weight. He talked with Lisa, who worked at AmeriCares Foundation in New Canaan, Conn., about getting supplies for his mission. "He was a very excited, compassionate young doctor...wanting to better mankind," Lisa Carlin remembers. They fell in love and, instead of going back to the Afghan border, as he'd planned, he joined her in Kenya to work on a reforestation project for three months. Back in the United States, Carlin did a three-year residency in emergency medicine at Morristown Memorial Hospital in New Jersey and then practiced in California and on the East Coast.

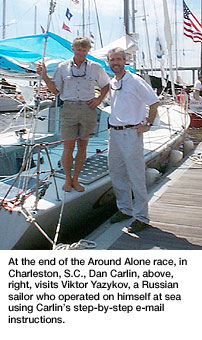

In 1998, he got his big media break, one that put him on the front page of The Boston Globe and launched him from there tointerviews with the British Broadcasting Corporation, South African national radio and "Ripley's Believe It or Not," among others. He appeared on "Dateline NBC," the Discovery Channel and "The Oprah Winfrey Show." How did he get all this attention? He sent e-mail instructions for self- surgery to a Russian sailor, Viktor Yazykov, who was participating in a solo race called Around Alone. Nine hundred miles from the African coast, the Russian sailor got in trouble. "I remember thinking after writing that e-mail, this guy has all the preconditions for dying at sea," Carlin says. "His boat had just suffered a major structural failure, he's physically exhausted, he's sick and now he's got to do something fairly dramatic just to save his life." With voice communications lost, Yazykov's only lifeline was the boat's satellite e-mail system. Following Carlin's typed instructions, Yazykov lanced the crippling abscess on his arm. He wrote back to Carlin that the wound was bleeding profusely. With one simply worded e-mail after another, Carlin told Yazykov how to stop the bleeding. The sailor did, and he recovered. The story resonated because "this guy is so damn alone, so isolated, and at the end of his rope, in a tough situation, and the Internet reaches out and touches that little boat floating in the middle of this huge gale," Carlin says. "And some guy so far away in the comfort of his office in Boston is saying, 'I need you to cut through your arm....'" It takes a special kind of patient to operate on himself. Circumnavigators are that type, but most of Carlin's traveling clients expect more routine care. Eighty to 90 percent of his contacts are by phone rather than e-mail. When Carlin needs to make a referral, he calls the doctor he is referring a patient to, describes the case, expresses his concern and requests a report back, being careful to do this without seeming heavy-handed. "A lot of medicine happens on a colleague-to-colleague basis, and if you keep it on that level, it generally works really well," he says. Tom and Louisa Shields of Burlingame, Calif., relied on WorldClinic and have never regretted the expense. They signed up before launching their yearlong around-the-world honeymoon in the year 2000. WorldClinic doctors helped each of them through a bout of food poisoning and Louisa with an eye infection, directing them to antidotes in their medical kits. Their most alarming experience came, though, in Uyuni, Bolivia, which the guidebooks had cautioned was not a place to get sick.

"The voice of Dr. Carlin at first terrified me, and then it totally calmed me down," she remembers. Back at the hotel, she gave Tom the prednisone from their medical kit that Carlin had prescribed. This reduced his pain, enabling him to breathe more deeply. She pleaded with the hotel keeper to get them a seat on the next bus, which required bumping another passenger. In the next 14 hours, they descended 7,500 feet. Tom's condition improved at the lower altitude, but Carlin remained in touch over the next few days to monitor his progress. "They were my calming agent," says Louisa, a management consultant, about WorldClinic. "We'd head off into the middle of Laos, and I always knew that at the end of any phone, we'd have whatever medical help we needed. That let my husband go on greater adventures because I wouldn't mind."

He dreams of Web communities for "orphan diseases" Although World-Clinic raised $3.75 million in private equity investing, it never progressed to the point of making a public stock offering. "We spent our money, and we were going to raise a second round of money, and then the tech market collapsed," Carlin says. He blames some of WorldClinic's problems on other Internet medical sites that he believes poisoned the market because they delivered more hype than science. Last August, he rescued WorldClinic by reacquiring it from investors and assuming its liabilities. "It's not a big company. We have four to five people, depending on what day of the week it is. "The irony of all this is that we've renewed about 90 percent of our business, and we've acquired three more clients," Carlin says. "So our little company is now doing well.... It's a way to support my family, in a fairly modest way at this point, but it gives me a springboard to do a bunch of other stuff." He and Lisa, who live in Wilmington, Mass., have four daughters, Alexa, 10, Savannah, 7, Rive, 5, and Tessa, 7 months. "It was very difficult, and we've made a lot of sacrifices for it to work," Lisa Carlin says. She hopes WorldClinic will eventually prove profitable enough that she and her husband can return to the mission of their youth. She would like to do overseas aid work a few months a year. When they were in Africa, she remembers, treating a man's leg wound could prevent an ulcer and amputation. "It's truly lifesaving work," she says. Daniel Carlin also looks forward to doing more nonprofit work. He plans to create Web communities for patients with "orphan diseases" that don't get much attention from researchers. Monitoring the treatment and condition of children with the rare Ollier's disease, for instance, would make each sufferer around the world part of a study cohort and give doctors a better idea of the factors that determine survival. "Imagine this analogy," Carlin says. "You're given a haystack. It's got 6,000 straws, and now a helicopter scatters that haystack over the whole world. With the Internet, you can reassemble the haystack, and you can find the needle." Early this year, he became president of an existing organization, the Ollier/Mafucci Self-help Group, which has 500 members worldwide. In another medical use of the Internet, Carlin wants to monitor people with chronic diseases so doctors can adjust treatments for asthma, diabetes or high blood pressure on an as-needed basis, averting crises.

It's ironic that one of the reasons Carlin became involved with Internet-based medicine is that he saw himself as someone who could close the growing distance between patients and physicians. Asked how many of his patients he has actually met, he has to think. "Not many," he says. "A fraction." Then a story comes to mind, another tale in which his patients are as vivid as if they had once sat on an examination table in front of him. "You may never meet them but, my gosh, when you answer the phone, and it's a mother with a sick kid, and they're in Indonesia, and it's the third call as you're tracking the child, you get bonded."

> Back to the top > Back to Carnegie Mellon Magazine Home |

|||||

|

Carnegie Mellon Home |

||||||

When Daniel J. Carlin describes the airlifting of a sailor off a Navy cruiser, his eyes gleam. It's a tale of risks to both life and ego. He was the ship's chief medical officer, not long out of Tufts University School of Medicine. The sailor was suffering from acute appendicitis. To save him, the captain had to stop chasing a Russian submarine in the South Atlantic Ocean, which he was loath to do. If Carlin was wrong about the sailor's condition, he would lose the respect of the captain and his shipmates.

When Daniel J. Carlin describes the airlifting of a sailor off a Navy cruiser, his eyes gleam. It's a tale of risks to both life and ego. He was the ship's chief medical officer, not long out of Tufts University School of Medicine. The sailor was suffering from acute appendicitis. To save him, the captain had to stop chasing a Russian submarine in the South Atlantic Ocean, which he was loath to do. If Carlin was wrong about the sailor's condition, he would lose the respect of the captain and his shipmates.

Continuing demands on U.S. senior managers and technicians to travel widely bode well for WorldClinic. "People won't do that unless their health care can be protected, and this fits that niche," Moyer says.

Continuing demands on U.S. senior managers and technicians to travel widely bode well for WorldClinic. "People won't do that unless their health care can be protected, and this fits that niche," Moyer says.

He tells a Russian sailor how to operate on himself

He tells a Russian sailor how to operate on himself When they arrived in Uyuni late at night by bus, Tom's teeth were chattering. By 5 a.m., barely able to breathe, he told Louisa he thought he had altitude sickness. Louisa went out onto the street to look for a coin-operated phone. With only enough change to cover a 60-second conversation, she reached Carlin and described Tom's symptoms. "You have to get him down. You have less than 36 hours before he's gone" were the last words she heard from Carlin before she was cut off, she recalls.

When they arrived in Uyuni late at night by bus, Tom's teeth were chattering. By 5 a.m., barely able to breathe, he told Louisa he thought he had altitude sickness. Louisa went out onto the street to look for a coin-operated phone. With only enough change to cover a 60-second conversation, she reached Carlin and described Tom's symptoms. "You have to get him down. You have less than 36 hours before he's gone" were the last words she heard from Carlin before she was cut off, she recalls.