|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

Videos about Work and Workers What Can Students Learn From a Pittsburgh Steelworker? To prepare students to operate in the real world, whether local or global, Paul Goodman and Denise Rousseau bring those worlds to the classroom through videos. By Ann Curran

This millwright doesn't appear live in a Graduate School of Industrial Administration classroom at Carnegie Mellon or in classrooms from the U.S. to Japan, from France, Ireland and Germany to Chile. He comes courtesy of a short video produced and directed by Paul S. Goodman, the Richard M. Cyert professor of organizational psychology in the business school, and Denise T. Rousseau, the

H. J. Heinz II professor in the Heinz School. The pair worked with consultants/photographers Ralph Vituccio and Tom Clancy at Carnegie Mellon in making the series.

Goodman and Rousseau, a married couple, followed an instinct to bring the "real world" into the classroom over a dozen years ago. Since, they have produced close to 20 videos focused on individual workers, similar to Studs Terkel's book "Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do." Goodman sees Brazilian photographer Sebastian Salgado's "Images of Brazilian Workers" as a major influence in his work. The videos include "Waitress," "Nurse," "Lobstermen," "University President" (it's Carnegie Mellon's late President Richard M. Cyert); "Stone Carver," among others. The videos have focused, too, on groups of workers: "Chinese String Quartet," "Chamber Music Quartet," "CERT" (formerly known as the computer emergency response team at Carnegie Mellon), "Rowing in an Eight" (women's crew at Cornell University).

Bernie Leppold, a part-time university employee, handles the business end on her own time. When orders come in, she calls up New Media Inc., Downtown; they dupe the video and send it out to customers along with the teachers' notes and a guide to the Web page (www.workvideos.com). The hardest part of the business, says Rousseau, "is figuring out how to put in the credit card information when you're just a family business. They keep changing the software." Only recently has the couple branched into full-length documentaries, beginning with one on a unique group of workers called "Dabbawallas" in Mumbai, India. They're aiming this longer work (see sidebar) at a general audience.

So what do students learn from the steelworker?

Nurse video shows an expert at work

"Everybody knows what a nurse does," she says. Rousseau can use the video with "people who have incredibly varied organizational experience from zero to maybe a 30-year career."

The nurse, clearly an expert, works in a field that has changed over the years. Nurses have more responsibility, more authority than in the past, the video details. This nurse knows her actions on the job are often "a matter of life and death." But she also knows, "I can do a good job with a child [in danger of] dying. I know exactly what to do." She prides herself on taking the extra step, doing more than is expected, "making sure parents understand how the kid is doing." She knows, too, that for self-preservation, "when you walk out the door, you leave this behind."

Rousseau writes the teachers' notes that accompany each video. They guide professors to use the videos in multiple ways. Goodman refers to his wife as "one of the best teachers in this university, without question," and her students use adjectives such as "energetic" and "enthusiastic" in describing her. "I might see a video [as illustrating] autonomy and control," says Rousseau. "Somebody else sees it reflecting standards of excellence. Somebody else might see conflicts. Somebody else might see an important issue in training a nurse."

Rousseau used the video "Plant Closing" in her Organizational Change course to typify the breaking of a psychological contract. Workers at Nabisco, a cracker/cookie producing company in Pittsburgh, who thought they had "a job for life," found out by reading the newspaper that their plant was closing. Tara Trapani, who took Rousseau's course, said she learned from the video that before the closing, "management listened to workers and gave incentives" for suggestions on how to improve. Costs were cut; production was up. In fact, on the day the plant closed, the company was operating at 105 or 106 percent of production, Goodman adds. Trapani said she was "extremely moved, angered and outraged" by the company's decision to close without informing employees. Both she and classmate Bridget M. Jakub planned to boycott Nabisco products made at other locations. As future managers, both students learned to look at actions from the point of view of the worker.

Policing the Internet is a new kind of job

Rousseau has used the "CERT" video in many different ways: for managing across boundaries (among people with different disciplines); group decision-making; managing a meeting; handling conflict. "And, if I frame it correctly," she notes, "the students will come up learning things that I didn't see but that reflect their own experiences and generate conversations in the classroom. It applies the concepts that we're talking about in class but also works the students' experience and then the new experience in the film. It's so cool!" says Rousseau. "It's always different."

We're pulling in the traps. Then he goes to another place and doesn't pull them out. And I have no idea why." In a follow-up video, "Lobstermen II," the father and son install a Global Positioning System in their boat. This means they can go out in fog or at night and find their 1,500 traps. It also means there's a computer record of where the traps are placed, the date when they are set, when they are pulled out, what the yield is. As a result of the application of technology to the task of lobstering, the son can construct a spreadsheet from the information gathered and learn a lot more about the knowledge that his father has but really can't explain. On the fourth day after installation of GPS, the Johnsons hauled in $1,000 worth of lobster.

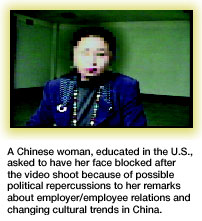

Some videos expand global awareness While Goodman and Rousseau were guest-teaching at the Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, people there knew they had already made a video about Cuarteto Latinoamericano, a string quartet in residence at Carnegie Mellon's School of Music. So they were invited to make a similar video about the Huqin Quartet, a Chinese group. Goodman found the Chinese quartet to have a distinct entrepreneurial spirit, reflecting the buzzing economy in Singapore. They were not playing traditional music or instruments. Goodman suspects the quartet's method of work might resemble "what work will be like in the future. A string quartet only works maybe once a week. They spend most of their time practicing.... They are not coming to work every day, five days a week, at a particular time. Other times they are thinking, reading or practicing." Even more than many working teams, a quartet must set aside its personal differences and work as one. The beauty is in the blend. Some of the working videos focus students' attention outside of the U.S. The Mexican video, "Doing Business in the U.S. and Mexico," is set at FRISA, a specialty steel company in Monterrey, Mexico. With this company, global relations are imperative. Only 10 percent of its products are sold in Mexico. The video contrasts the work force at FRISA versus a similar group in the U.S. The Mexican workers come from the countryside. Workers and their supervisors are often people who grew up together. As a result there's less of a line between them, even though there's a greater disparity in wages. And there's closer supervision of workers. Some workers have not completed primary or secondary school and take classes at the workplace. The company president says his workers "want their children to have a better life." He describes one worker who completed his primary school work and was pleased that he could now help his children with their homework. If you subtract the accent from the Mexican company president, Goodman says, "the way he talked about the customer, what he did about the customer, how responsive he was, that should be said by any good manager anywhere.... That's a generalizable thought that would cross all kinds of cultures." Only in one videotape did Goodman and Rousseau have to apply some censorship. In "Reflections on Changes in China," they interviewed a Chinese woman who was educated in the U.S. and worked for a Chinese firm. When she went back to China to work, she was stunned by the fact that employees were not expected ever to challenge employers. "After we had shot the film, she came back the next day, crying," says Goodman. The woman said, "I told my parents what I did. Can't you block my face?" The videographer did that, and Goodman says it "actually makes it more powerful." The woman's comments suggest that rules and regulations within the company can bend "under the table"; that "everybody is talking about money and how they can get rich.... They are more consumer-oriented." Previously, the family prevailed; "now there are divorces and remarriages." Goodman made his first video at age 14. His decade of making short educational films has led, perhaps inevitably, to the production of "a stand-alone piece that is a story that can be informative to people." It's called "The Dabbawallas," a group of 4,000 men who deliver 100,000 lunches from private homes to workplaces each working day all over Mumbai, India. Goodman is always on the lookout for interesting forms of work. He heard about the dabbawallas on a visit to Mumbai. An Indian producer helped the couple connect with the group.

But the educational videos continue. The couple is focusing on migrant workers picking blueberries in Maine. Yes, Goodman and Rousseau have an affinity for Maine. They were married on Eagle Island there. The blueberry pickers will raise questions "about marginal workers and social responsibilities." And Goodman is busy planning another documentary. This time on one of the work groups that stages Rio de Janeiro's annual pre-Lenten explosion of merriment, music, dance and madness called Carnevale.

> Back to the top > Back to Carnegie Mellon Magazine Home |

||||||

|

Carnegie Mellon Home |

|||||||

A Pittsburgh steelworker is making appearances at Carnegie Mellon and at 150 other universities across the globe. Like his grandfather and father before him, he works at Edgewater Steel Company in Oakmont, Pa. He fixes broken things all over the plant. He picked his job for the variety it offers. He talks about the "great camaraderie working in a place like this." He pushes himself to be a better mechanic even when others are standing around, slacking off, drinking coffee. He laments that the industry has collapsed; the company has changed ownership too often; it's failed to invest in the plant; it erred in putting its profits into a non-union facility down south. He's worked 30 years at Edgewater and says the retirement benefits are terrible. "I could never survive on the money." As it is, he can't live on the money he's earning. He "can't take a vacation." He "can't go out once or twice a week." He "can't afford to play golf."

A Pittsburgh steelworker is making appearances at Carnegie Mellon and at 150 other universities across the globe. Like his grandfather and father before him, he works at Edgewater Steel Company in Oakmont, Pa. He fixes broken things all over the plant. He picked his job for the variety it offers. He talks about the "great camaraderie working in a place like this." He pushes himself to be a better mechanic even when others are standing around, slacking off, drinking coffee. He laments that the industry has collapsed; the company has changed ownership too often; it's failed to invest in the plant; it erred in putting its profits into a non-union facility down south. He's worked 30 years at Edgewater and says the retirement benefits are terrible. "I could never survive on the money." As it is, he can't live on the money he's earning. He "can't take a vacation." He "can't go out once or twice a week." He "can't afford to play golf."

The "Steelworker" video is part of a series called "The Changing Nature of Work," purchased by some of Goodman and Rousseau's customers for use in assorted courses such as business, sociology, psychology, social work and nursing. The videos range from 15 to 30 minutes in length and sell for $80 to $100.

The "Steelworker" video is part of a series called "The Changing Nature of Work," purchased by some of Goodman and Rousseau's customers for use in assorted courses such as business, sociology, psychology, social work and nursing. The videos range from 15 to 30 minutes in length and sell for $80 to $100.

Other videos developed by the academic couple for their own mom-and-pop sideline examine more typical business school fare: a Mexican specialty steel company; organizational change with Rousseau as the on-camera teacher; managing in China; a plant closing in Pittsburgh.

Other videos developed by the academic couple for their own mom-and-pop sideline examine more typical business school fare: a Mexican specialty steel company; organizational change with Rousseau as the on-camera teacher; managing in China; a plant closing in Pittsburgh.

"It's important for students who are thinking about the new economy to understand workers who have committed their lives to an organization," says Goodman, who early in his career studied coal mining crews in the U.S. "It's also a good example for middle-class and upper-middle-class students to realize that workers like that are actually very articulate about economics and what's going on in the marketplace." And, he observes, listening to the steelworker helps to erase some of the stereotypes students might have about such workers. One of Goodman's customers, Terri L. Griffith, management professor at Santa Clara University, agrees. She teaches intrinsic motivation and equity theory with the video and finds students "are surprised to see the love this guy has for his work and the challenge of learning something new."

"It's important for students who are thinking about the new economy to understand workers who have committed their lives to an organization," says Goodman, who early in his career studied coal mining crews in the U.S. "It's also a good example for middle-class and upper-middle-class students to realize that workers like that are actually very articulate about economics and what's going on in the marketplace." And, he observes, listening to the steelworker helps to erase some of the stereotypes students might have about such workers. One of Goodman's customers, Terri L. Griffith, management professor at Santa Clara University, agrees. She teaches intrinsic motivation and equity theory with the video and finds students "are surprised to see the love this guy has for his work and the challenge of learning something new."

Such a range of experience is not infrequent among Heinz School students, Rousseau says. There are students who have worked as managers for many years, and there are others "who have been students all their lives.... Maybe they've been sent by their government overseas to get some training before they go to work in that government."

Such a range of experience is not infrequent among Heinz School students, Rousseau says. There are students who have worked as managers for many years, and there are others "who have been students all their lives.... Maybe they've been sent by their government overseas to get some training before they go to work in that government."

Students working with the nurse video could easily examine stress management, the burnout rate for nurses as well as others in demanding jobs (executives, air traffic controllers, Pittsburgh Steelers, etc.). They might discuss what causes burnout and ways to avoid it. Rousseau is modest about her involvement in the project. "I'm basically sort of like the trampoline for him [Goodman] to bounce ideas off of, and from time to time I suggest, 'Wouldn't this be great if we had a film on x?'" Many of their films are shot in Pittsburgh; others, at places Goodman has traveled to for the university.

Students working with the nurse video could easily examine stress management, the burnout rate for nurses as well as others in demanding jobs (executives, air traffic controllers, Pittsburgh Steelers, etc.). They might discuss what causes burnout and ways to avoid it. Rousseau is modest about her involvement in the project. "I'm basically sort of like the trampoline for him [Goodman] to bounce ideas off of, and from time to time I suggest, 'Wouldn't this be great if we had a film on x?'" Many of their films are shot in Pittsburgh; others, at places Goodman has traveled to for the university.

Even more non-traditional is the

Even more non-traditional is the  The couple made two videos on Maine lobstermen, the father- and-son team of George and Carl Johnson. In the first video, Goodman ran into—as he often does—the unexpected: what he describes as the difference between explicit and tacit knowledge. (Explicit, you can share; tacit is Grandma's unmeasured recipe that nobody can duplicate.) The son tells Goodman, "I'm out with him [his father] every day. We set these traps the day before.

The couple made two videos on Maine lobstermen, the father- and-son team of George and Carl Johnson. In the first video, Goodman ran into—as he often does—the unexpected: what he describes as the difference between explicit and tacit knowledge. (Explicit, you can share; tacit is Grandma's unmeasured recipe that nobody can duplicate.) The son tells Goodman, "I'm out with him [his father] every day. We set these traps the day before.

Plenty apparently, says Paul S. Goodman, who along with Denise Rousseau, has produced and directed their first full-length documentary, called "Dabbawallas," aimed at educational stations in the U.S. and abroad. The word "dabbawalla" translates from Marathi as "box person" and describes people who pick up lunches made in an employee's home, take them to workplaces all over Mumbai, India,

collect the empties and take them home again each day.

Plenty apparently, says Paul S. Goodman, who along with Denise Rousseau, has produced and directed their first full-length documentary, called "Dabbawallas," aimed at educational stations in the U.S. and abroad. The word "dabbawalla" translates from Marathi as "box person" and describes people who pick up lunches made in an employee's home, take them to workplaces all over Mumbai, India,

collect the empties and take them home again each day.