|

|

||||

|

|

Autonomous "Groundhog" Maps Mathies Mine

�

Carnegie Mellon University's Groundhog, an autonomous, four-wheeled robot with huge heavy duty tires, took an unprecedented trip into an abandoned coal mine in late May and was able to create accurate three-dimensional maps of its surroundings (http://www-2.cs.cmu.edu/~thrun/mines/mathies/index.html).

Students in the Robotics Institute's Mobile Robot Development class, taught by Systems Scientist Scott Thayer and Fredkin University Professor William L. "Red" Whittaker, developed the robot in response to an incident at the Quecreek Mine near Somerset, Pa. last July, when nine miners nearly drowned when they accidentally breached the wall of an adjacent flooded mine. Inaccurate maps were cited as a cause of the accident.

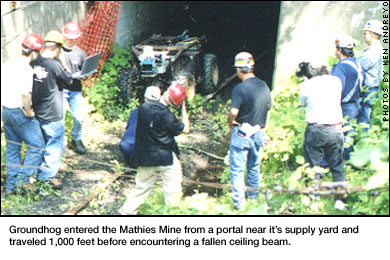

Groundhog's goal was to explore and map a 3,500-foot corridor of an abandoned coal mine near New Eagle in southwestern Pennsylvania. Overseeing the excursion were the Carnegie Mellon control team and officials from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) and the U.S. Department of Labor's Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA).

The robot entered the mine from a portal near its supply yard and traveled slowly into the mine at a speed of 1 mile per hour. About 1,000 feet into the mine, Groundhog, which sends its robot-eye view back to the control team through a wireless video system, encountered a fallen ceiling beam that crossed its path. It made the appropriate decision to retreat.

"The level of autonomy necessary to achieve this mission was remarkable," said Associate Computer Science Professor Sebastian Thrun, who contributed his site localization and mapping technology to the project.

"Groundhog exhibited state-of-the art perception, planning reasoning and navigation," said software developer and student Dave Ferguson. "It's choice to turn around after encountering the ceiling beam was the result of a careful geometric analysis based on which the robot concluded it would be unsafe to try to bypass this obstacle. Of course, when developing the robot, we had no clue what to expect, so we could not develop special purpose rules such as if you encounter a ceiling beam."

Groundhog is armed with an array of cameras, gas, tilt and sinkage sensors, laser scanners and a gyroscope to help it surmount the mine obstacles it encounters, such as roof fall, abandoned equipment and ponded water. Using perception technology to build maps from sensor data, it must make its own decisions about where to go, how to get there and, more important, how to return safely.

Reliable navigation technology is important because of the many hazards in abandoned mines. The robot also contains computer interfaces that enable people to view the results of its explorations and use the maps it develops. Groundhog incorporates a technique developed at Carnegie Mellon called Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM), which enables robots to create maps in real-time even as they explore an area for the first time.

Robotics Institute students first demonstrated Groundhog last fall at a mine near Burgettstown, Pa. The robot, then on a tether, traveled 150 feet into the facility that had been abandoned since 1920. That expedition proved the feasibility of using mapping technology to explore abandoned mines.

"Because it's autonomous, Groundhog represents one of the real junctions in robotics technology," Whittaker said. "The Groundhog is only the beginning. We see future generations of machines that will swim, crawl and climb through mines to enhance safety, support rescue and ultimately enable robotic operations beyond mining in caves, bunkers, aqueducts and sewers."

The DEP has given Carnegie Mellon researchers a grant to develop another robot called Ferret, a cylindrical device designed to be dropped through boreholes into a void. It uses a laser rangefinder to build three-dimensional maps of an otherwise inaccessible space.

"The Commonwealth is committed to researching new technologies that can help us map abandoned mine workings, and we are pleased to partner with Carnegie Mellon University's Robotics Institute as they explore the possibility of sending a robot in to map the extent of these mine voids," said DEP Acting Secretary Kathleen A. McGinty. "These are areas out of reach to those of us on the surface, but if we can use robotic technology to chart these workings, then we will have gained an invaluable tool in our efforts to protect the miners of the Commonwealth from facing another tragedy such as the Quecreek Mine accident."

Anne Watzman

|

||

|

Carnegie Mellon Home |

||||

During its retreat, Groundhog had to reboot its computer system several times for reasons still unknown. Two safety officers from the DEP entered the mine to reset the robot's data transceiver. The robot's control team then reestablished communication and guided the robot out of the mine and back to its control truck under the robot's own power.

During its retreat, Groundhog had to reboot its computer system several times for reasons still unknown. Two safety officers from the DEP entered the mine to reset the robot's data transceiver. The robot's control team then reestablished communication and guided the robot out of the mine and back to its control truck under the robot's own power.

"Groundhog has to be ultra-reliable because we don't have the option of taking control of it to correct its mistakes," Thayer said. "The key is our state-of-the-art autonomous exploration and mapping software technology. The robot creates the map, makes its own plan, explores and comes back with useful information."

"Groundhog has to be ultra-reliable because we don't have the option of taking control of it to correct its mistakes," Thayer said. "The key is our state-of-the-art autonomous exploration and mapping software technology. The robot creates the map, makes its own plan, explores and comes back with useful information."