The Birth of Frozen Orange Juice

In the early 20th century, scientists and industrialists viewed each other with a wary eye. But Robert Kennedy Duncan, a chemist and professor, thought that should change, and with the financial backing of Andrew and Richard Mellon, Duncan founded the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research, where scientists worked to solve the problems of industry.

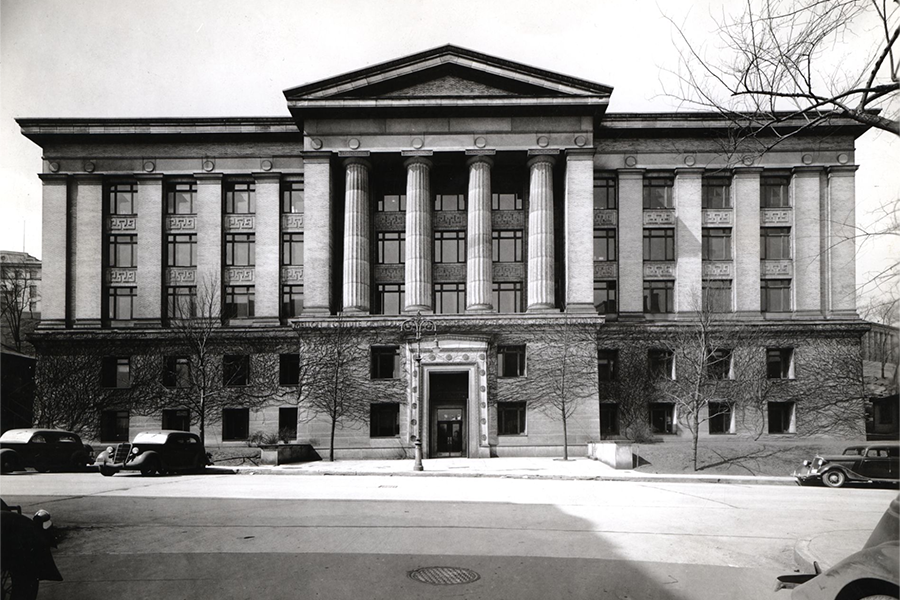

From 1913 until 1967, when it merged with Carnegie Tech to form Carnegie Mellon University, the Mellon Institute, took on problems large and small. It is where the processes that made frozen orange juice, razor blades and skinless hot dogs possible. The institute also spent many years investigating the issues of air quality in Pittsburgh and the health and occupational well-being of lab and factory workers.

Here are three things you may not know about the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research.

Each of the Mellon Institute’s columns is 36.5 feet tall and nearly six feet in diameter at the bottom.

Each of the Mellon Institute’s columns is 36.5 feet tall and nearly six feet in diameter at the bottom.

They were quarried from 125 ton blocks of limestone brought from Indiana (and it’s a myth there’s one buried near the site). Many of the doors and windows throughout the building are made of aluminum.

The Mellon Institute contributed to many war efforts.

The Mellon Institute contributed to many war efforts.

The first gas mask used during World War I was developed at the Institute, and during World War II the Institute participated in the successful development of synthetic rubber.

More than 650 novel processes and products were invented or developed by Institute fellows during its tenure.

This includes tons of common things like beverage flavors, breakfast cereals, edible gelatins, fertilizers, glues, inks, insecticides, shoe leathers, skinless hot dogs, frozen orange juice, razor blades and fluoride.