|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||||

|

East Meets West Tongue Tells Health Tales Researcher Yang Cai wants a computer to see and evaluate tongues as Chinese medical experts might. By Ann Curran

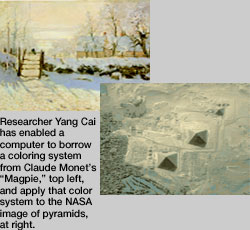

The TCM doctor wants to see the tongue, its shape, the color of both the tongue and its coating, its texture, how it moves—regardless of the patient's illness or lack of illness. Tongues can vary all over the place with coatings, called fur, that are thin, thick, white, yellow, red, pale, dark, gray, black, greasy, etc., and with the tongue body or muscle running into shades of red, blue, purple and black. While Yang Cai, a systems scientist and founder of the Biovision Lab in Carnegie Mellon's Human-Computer Interaction Institute, is a native of Suzhou, China, and recalls routine tongue examinations at the doctor's office, he was never totally into TCM. Practitioners of both TCM and "Western" medicine were available to him in China. "Western medicine is more dominant in China," he says. "People follow both. If your Western medicine's not working, you go to TCM." Studies in the National Library of Medicine's PubMed System indicate that increasing numbers of Americans—more than 40 percent—use complementary and alternative medicine. The National Institutes of Health, which houses and offers guidance through the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, defines a variety of practices and procedures under NCCAM as treatment by people not trained in medical schools, not offered in hospitals and not covered by health insurance. Cai's main research interest is computer modeling of human visual perception. That means he wants to teach computers to see the same things a person sees and make a judgment about what is perceived. He wants to simulate sight. However, he recently lost a best friend to ovarian cancer at age 32, and his aunt died of brain cancer four months after diagnosis. Neither cancer provides much in the way of early warnings. So Cai paid attention when a Carnegie Mellon visiting professor in materials science and engineering, Mei-qing Huang, pointed him in the direction of examining the tongue as an early indicator of certain cancers. The subject fell within his interest in simulating sight. He imagined a computer program capable of looking at the human tongue as a TCM expert would. Huang's husband, Jin-song Chen of the Science and Technology University in China, showed Cai a couple of photos of cancer patients' tongues. "I didn't believe it until I saw those pictures," Cai exclaims, describing a bit of a eureka moment. The images showed a correlation between the tongues' appearance and certain cancers.

Study links tongue changes to various cancers

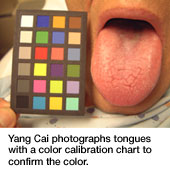

Formerly associated with the now dismantled Carnegie Mellon Research Institute, Cai says that through the "reorganization" of that division, "I have gone through lots of changes, but I have kept my tongue project." Now operating under the wing of the Human-Computer Interaction Institute, Cai received a Berkman Faculty Development Fund award and support from the Jewish Healthcare Foundation. He's bankrolled the tongue project with his own funds, too. Cai asks a big question about his application of Western scientific methods to TCM: "Can computers do the job as well as human doctors?" An initial problem is color perception. He is using a digital camera to photograph tongues under a consistent light. Using the camera and photographs makes the job more difficult for a computer, says Cai. "You have to remove the shadows, make sure about the true color." In addition to collecting tongue images in Pittsburgh, Cai has provided a camera and instructions for Xingming Lin of Anhui Medical School in China. Lin oversees an 80-bed unit for cancer patients. Earlier, Cai, working with a hand-held scanner, had devised what he calls "the world's first tongue scanner." It turned out that the scanner was too wide by an inch or so to scan a person's tongue comfortably. In addition, light and color were not an issue in using it to scan tongues but sanitation was. The cost of manufacturing test throwaway tongue scanners forced Cai to move to the digital camera.

Tongue project proceeds in cooperation with UPMC Cai began collecting tongue images from Schoen's patients in April at Presbyterian University Hospital. Working with research nurse Karen Foley, Cai takes two photos of a patient's tongue with a color calibration chart in the photo. On the computer, Cai uses software to extract the tongue from surrounding features. He maps color, texture and shape to form a mathematical model, representing the tongue digitally. Cai's participation in Schoen's study has enabled him to collect images in a scientific way. All the patients involved are preparing for a colonoscopy, an examination of the inside of the large intestine. They don't eat for at least five or six hours before the test. There's no chance of their having a cherry or lime Popsicle before the tongue photo that would affect the actual tongue color. In addition, Schoen will share with Cai where patients end up healthwise. The study identifies patients by number, not name, to protect their privacy. Schoen expects a mix of normal, precancerous and cancerous results among the patients undergoing colonoscopy. Down the line, Cai envisions people holding an instrument the size of a Palm Pilot or wallet with a computer chip embedded in it. They'll stick out their tongue at it and get a diagnosis. "Not necessarily for cancer. Just health analysisŠa suggestion that they may need vitamins. It can tell you if you are stressed, dehydrated or [suffering an] imbalance."

He sees the computer images of tongues eliminating the subjectivity of tongue readings by various practitioners. He sees the possibility of a computer database of tongues that doctors might use to run comparisons with the tongue of a current patient. Or the telemedical possibility of sending the image of a tongue across the country or the world for examination and analysis by an expert.

Though he knows little about TCM, Schoen says, "From a clinical standpoint, it's not really much of a burden to the patients to stick out their tongue and have a picture taken." The computer images will isolate the tongue and become virtually anonymous, says Schoen, who sees the process as a noninvasive, easy add-on to his own study. While Schoen is impressed with the Chinese study of over 12,000 patients that showed a correlation between tongue characteristics and cancer—though it's in Chinese, and he doesn't read Chinese—he confesses that he's a skeptic. However, he notes, "If one could see some characteristics of the tongue correlated to the presence of adenomatous polyps that have the potential to transform into cancer, that would be great. Then you could just go around and take pictures of people's tongues. That's a lot simpler than doing colonoscopies." But he senses that that is a distant hope.

What's the advantage of tongue inspections carried out with a camera as an alternative cancer screening method? Cai is hopeful and clear on that. They are noninvasive, simple and inexpensive. And they may provide an early signal. That signal may do no more than lead a patient to Western medicine with its MRI, CT scans, X-rays and colonoscopies. But it's possible that the intervention could occur earlier and make for a more positive outcome.

> Back to the top > Back to Carnegie Mellon Magazine Home |

||||

|

Carnegie Mellon Home |

|||||

When a patient sticks out his tongue for a doctor in the West, chances are the physician is getting a good look at his throat. When a patient sticks out his tongue for a doctor who practices Traditional Chinese Medicine, the tongue is the point of interest. The tongue is one of the key examination sites in TCM as practiced in China, Pittsburgh or anywhere.

When a patient sticks out his tongue for a doctor in the West, chances are the physician is getting a good look at his throat. When a patient sticks out his tongue for a doctor who practices Traditional Chinese Medicine, the tongue is the point of interest. The tongue is one of the key examination sites in TCM as practiced in China, Pittsburgh or anywhere.

The literature on the subject, Cai reports, suggests that the tongue changes with tumor size. "When the tumor grows, the tongue gets more bluish [and has] more textural changes." But don't rush to the mirror. Reading tongues is a complex matter, and disagreement on the significance of tongue appearance can occur from TCM expert to expert.

The literature on the subject, Cai reports, suggests that the tongue changes with tumor size. "When the tumor grows, the tongue gets more bluish [and has] more textural changes." But don't rush to the mirror. Reading tongues is a complex matter, and disagreement on the significance of tongue appearance can occur from TCM expert to expert.

He leaps further ahead and suggests his findings might possibly become part of a "pervasive sensing" technology installed in a person's home—in a mirror, in a commode, in a scale, etc.—to make medical observations about the individual. Such monitors could send signals via computer to the person involved. For example, "You need to see a gastrointestinal doctor now." He likens the products to disposable intelligent devices, such as the $6 pregnancy kit anyone can pick up at a local drugstore.

He leaps further ahead and suggests his findings might possibly become part of a "pervasive sensing" technology installed in a person's home—in a mirror, in a commode, in a scale, etc.—to make medical observations about the individual. Such monitors could send signals via computer to the person involved. For example, "You need to see a gastrointestinal doctor now." He likens the products to disposable intelligent devices, such as the $6 pregnancy kit anyone can pick up at a local drugstore.

But over at the College of Fine Arts, they think of him as an artist. Last spring, you could visit a one-man show of his pastels at the Posner Hall Gallery at Carnegie Mellon. And he is a research fellow at the university's STUDIO for Creative Inquiry, housed in Fine Arts.

But over at the College of Fine Arts, they think of him as an artist. Last spring, you could visit a one-man show of his pastels at the Posner Hall Gallery at Carnegie Mellon. And he is a research fellow at the university's STUDIO for Creative Inquiry, housed in Fine Arts.