Cranor featured in The Washington Post

Big tech companies, such as Twitter and Facebook, have recently taken steps to make their privacy policies more digestible for thier consumers. However, the question remains: is simplifying privacy policies enough or should other methods, such as new laws and technology policies, be implemented so that consumers have more say over their privacy?

As an experiment, Washington Post journalist Geoffrey Fowler tallied up all of the privacy policies just for the apps on his phone to see how practical it was for users to read the data policies and agree to the terms and conditions for these apps — it totaled nearly 1 million words. “War and Peace” is about half as long. The deeper Fowler dug into them, the clearer it became that understandability isn’t our biggest privacy problem. Being overwhelmed is.

Back in 2008, Lorrie Cranor, a professor of engineering and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University, and a colleague estimated that reading and consenting to all the privacy policies on websites Americans visit would take 244 hours per year. She hasn’t updated the tally since but tells me that now you’d have to add in not only apps and connected gadgets such as cars, but also all the third-party companies that collect data from the technology you use.

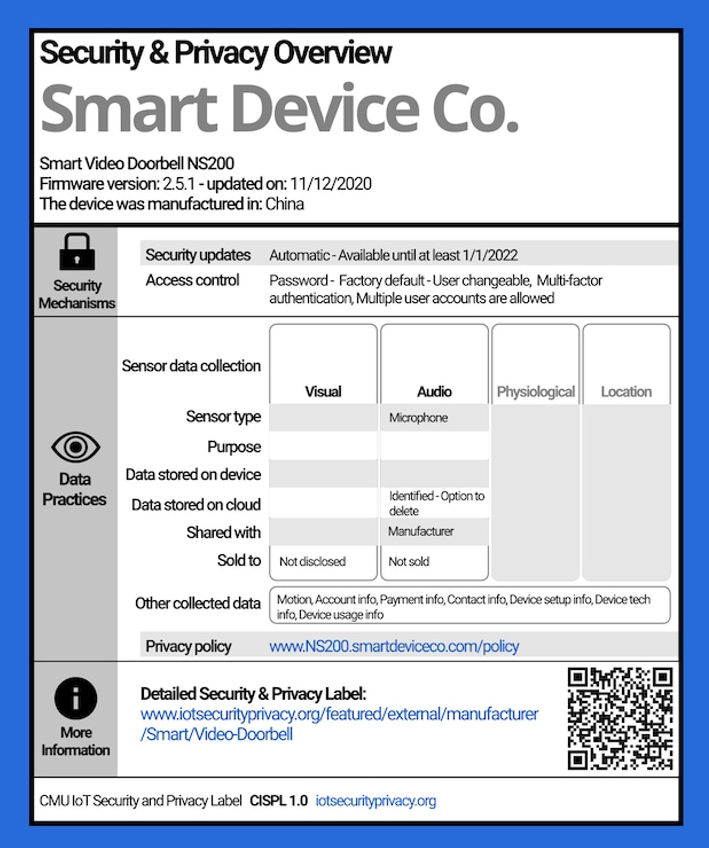

At Carnegie Mellon, Cranor has experimented with making privacy policies that look like the nutrition labels on packaged food. A label, she says, not only communicates quickly but also makes it easier to compare the practices of different websites and apps.

In January, a bipartisan group of lawmakers even introduced legislation that would require sites to make easy-to-digest summaries of their privacy terms. They called it the TLDR Act, a nod to the saying “Too long, didn’t read.”

But the devil is in the details. Few companies have made privacy labels that Cranor thinks actually do the job. “What’s most important to show to users is the stuff that will surprise them — the stuff that’s different than what every other company does,” she said. Both Apple and Google now offer app store privacy labels, but they’re not particularly clear or, as Fowler discovered, always even accurate.

In the article, Fowler presents the following as solutions: First, he proposes that we abolish the notion that we’re supposed to read privacy policies; Transform these policies into “data disclosures” for the regulators, lawyers, investigative journalists and curious consumers to pore over. Second, we need to replace the theater of pressing “agree” with real choices about our privacy. Apps and websites should give us the relevant information and our choices in the moment when it matters. Going a step further, Cranor suggests utilizing technology so that data disclosures could be coded to be read by machines. Finally, explore how technology might be able to protect our privacy in a world of connected devices like surveillance cameras, something that Cranor and her partners are working on.

Read the full article to learn more about privacy choices and policies.