|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||||

|

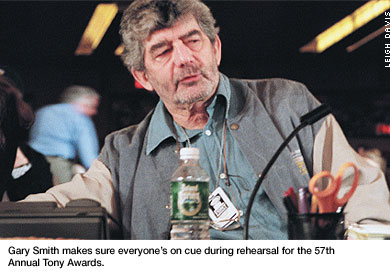

Behind the Scenes at the Tony Awards For executive producer Gary Smith, timing is everything. He makes the performers, the crew, the lighting, the sound and the graphics all come together—sometimes, at the last moment. � By Eric Sloss

Saturday, June 7 Smith stands in front of a grand piano swaying to the music, his hand on his chin, as he listens to the song "New York State of Mind." "Billy, that's great," he tells the player, who is the Piano Man himself, Billy Joel. Although few in the public might recognize Smith's name, in the entertainment industry, he is known as an innovator. His smile and kind heart make him a legend.

5:30 p.m.

Being in the elegant hall reminds Smith of another production, a show celebrating the Depression-era building's anniversary. One of the guests was Gregory Peck, who had once been an usher at the theater. "We took a camera way back on a huge long lens so there was a head-to-toe shot of Gregory Peck," Smith tells some members of the production crew. "We had him come up...and the camera started to widen and widen, and he did the same thing that he did when he was an usher." Smith swings his arm around and yells out, "Right this way is Radio City Music Hall!"

6:15 p.m. Smith's assistant reaches over her boss's shoulder to answer the phone. On the line is the assistant to Hugh Jackman, "The X-Men" film star who will host this year's awards, conveying the star's request for a healthy dinner that includes bagels. "Aussies eat bagels, too," Smith marvels. He reflects on all the things he needs to accomplish that weekend. "The best ideas always start here." He points to his heart. "If it doesn't start there, then you have nothing." Bob Dickinson, the show's lighting designer and an adjunct instructor in Carnegie Mellon's School of Drama, chimes in, "This has always been his trademark! Gary will drive us crazy. He will come into the truck and say, 'If we only did it this way.' This is after we rehearsed it. He'll say, 'But we've got to do it!' Sure enough, we'll make his changes and the production will snap to life." One such inspiration came to Smith as he was walking in New York and passed a street performer—a guy playing plastic cans. Thinking it would be a great idea to have the drummer create the rhythm music for the opening segment of the show, Smith asked him if he would like to be on TV. The drummer was so nervous during the shoot that Smith stepped forward to wipe the sweat from the man's forehead. Hours later, Smith's son Zach, who works with his father's Los Angeles-based production company, was editing the performance.

8 p.m. Afterwards, Smith gets onstage to offer tips to the young Def Poetry Jam performers, all of whom are in high spirits. The rain creates a glistening environment, reflecting the lights that surround Times Square.

8:50 p.m. The producer of the 57th Annual Tony Awards has rehearsed in many adverse situations. He's produced numerous awards ceremonies and other major events, among them a number of Democratic National Conventions, Emmy Awards and People's Choice Awards. He and his long-time collaborator, Dwight Hemion, have won 24 Emmy Awards for their work and have produced numerous television specials, including Elvis Presley's last performance and Bette Midler's first.

Sunday, June 8 "In rehearsal you need to get used to where everybody is. It really just starts to fly, even the logistics of the performance. The graphics are mind-boggling, the graphic package, play package, the way the winner walks up—it all comes together at the last second," Smith says.

9:30 a.m. Among the sets lined up backstage is the world's largest hairspray bottle, which will unload Harvey Fierstein for the "Hairspray" number. A driver brings in actors who care to rehearse. Danny Glover appears in a baseball cap and sweatpants and John Lithgow in jeans.

11 a.m. Smith is in front of a few monitors 14 rows back, stage left, flanked by his assistant and son Zach. Behind him sits Roy A. Somlyo, president of the American Theatre Wing. The American Theatre Wing and the League of American Theatres and Producers are the two organizations that present the awards. "Gary has a total vision for the show," Somlyo says. "He picks up on every single detail." On top of that, "he gets along with people so well. The key is to get your way but make sure people don't feel abused." One of the presenters rehearsing onstage, television interviewer Barbara -Walters, is dissatisfied with both her entrance and her script. Smith goes onstage to console her. He places his hand on her shoulder, and a couple of smiles and laughs later, she finalizes her run-through. "If you watched today, Barbara Walters did not want to do the material he gave her, and she substituted her own," Somlyo says. "Gary convinced her to try it our way." When she did, "she found out in front of the rehearsal audience that it was better, which we all knew." Walters agreed to use the script Smith had provided. "That's one of the classic examples of [Smith] dealing with people," Somlyo says. Smith's roots in the theater, along with his experience in television and set design, make him a logical choice to produce the Tonys, Somlyo says. "He has a New York point of view to things, regardless if he's based in California. He brings the California goods to the show, but doesn't let it get in the way of what's important to us—that our audience is seeing Broadway. That's why he's the best."

1 p.m. Smith instructs performers doing selections from the Broadway plays "Gypsy," "La Boheme" and "Hairspray" to ensure they will execute the numbers on time. Some people come to the rehearsal to catch a few stars in sweatpants, see how the show is pulled together and discover how Smith smooths out the rough edges. Most of them sit in the second tier of the theater while those with the right credentials are admitted to floor seating. CBS agreed to broadcast the entire three hours of this year's awards ceremony, and that created an opportunity for Smith to do some creative programming. "I interviewed everyone who's nominated: Brian Stokes [Mitchell], Bernadette [Peters], so you hear directly from them. So Brian Stokes says what it's like to play Don Quixote. They will do an interview that the audience will see. Then we will transition into the numbers." Carnegie Mellon interns Noah Mitz, a junior in drama, and Evan Purcell, a senior, walk across the stage with lighting designer Dickinson. Somlyo, who's been in the business even longer than Smith, remembers kids fresh out of the Carnegie Institute of Technology coming to Broadway decades ago. "You would get the kids backstage and let them see the electricians and equipment and lighting," he says. "What is this?" they'd ask when they saw the old-fashioned piano boards. "They would say 'This is all the lighting you have! How do you light a show with these limited facilities?' They were so spoiled by the technology they were getting in college. They had to make the adjustment. By the time they made the adjustment, the new crew [of students] came in and said, 'Where are your computers?' Carnegie Tech was the place to go."

Other Carnegie Mellon alumni besides Smith have a stake in the outcome of the Tony Awards. Brad Dean (A'93) plays Anselmo in "Man of La Mancha." The production was nominated for best revival of a musical. Dagmara Dominczyk (A'98) plays Lady Caroline in "Enchanted April," which was nominated for best play, and Frank Gorshin (A'55*) plays George Burns in "Say Goodnight, Gracie," also nominated for best play.

6 p.m. Cameras flash and the crowd screams as each star hits the carpet. Two policemen, there to make sure that the media does not get out of hand, wave to Billy Joel and give him a thumbs up. Joel waves back. Philip Seymour -Hoffman, Laurence Fishburne, Chita Rivera, Edie Falco and Mary Stuart Masterson and many other stars all cross the red carpet into Radio City Music Hall.

7 p.m. In a makeshift living room area behind a large-screen TV, Bebe Neuwirth and Ann Reinking sit on an ottoman, sipping wine. They occasionally get up and practice the choreographed number they will do as they walk out onstage to present the award for best choreography. After the first hour, Smith goes out to warm up the crowd, making them laugh, as he commonly does with his production crew. He instructs the crowd not to stand in front of the large-screen TV that scrolls the scripts for the award presenters.

9 p.m. Matthew Broderick comes backstage with his wife, Sarah Jessica Parker, on his arm. A television screen catches his eye, and he pauses to watch Langella onstage while Sarah moves on to get the trade-show sales pitch. Antonio Banderas and Melanie Griffith are whisked backstage by an entourage of folks dressed in black and headsets. Melanie stands a touch taller than Antonio. She's wearing a Versace dress soon to be made famous by the paparazzi. On her arm is a black-heart tattoo with the name Antonio branded inside.

10:15 p.m. During commercial breaks, everyone stretches or chats. Smith is heard over the speaker, saying the production is running behind.

11 p.m. "Among the most attractive things about someone in our profession, especially those who've been at it a long time, is their commitment, dedication and passion," actor Langella says. "Gary is a success because he still loves what he does and loves it as though it were the first time he was doing it."

Eric Sloss is the associate director of media relations for Carnegie Mellon's College of Fine Arts.

�

> Back to the top > Back to Carnegie Mellon Magazine Home |

||||

|

Carnegie Mellon Home |

|||||

Smith is working through the scheduled meal break. On his way to his makeshift office on the second floor, he stops to say hello to the 4-year-old daughter of one of the crew members, who clings shyly to her mother, then returns his smile.

Smith's title is executive producer, but his job is not easy to define. It is fluid and broad, encompassing an impossible range of talents and responsibilities. What he has to do, he says, is to take what an artist is about, what the theme of the show is about, and what the intended purpose is, and create a television production that allows these elements to come together.

A large production like the Tony Awards requires attention to every detail. But, says Smith, "the biggest concern is always time." Sometimes people ask him whether he worries that something unexpected might happen during a live show. "You want the production to be spontaneous," he tells them. "Sometimes you can set that up."

Smith is working through the scheduled meal break. On his way to his makeshift office on the second floor, he stops to say hello to the 4-year-old daughter of one of the crew members, who clings shyly to her mother, then returns his smile.

Smith's title is executive producer, but his job is not easy to define. It is fluid and broad, encompassing an impossible range of talents and responsibilities. What he has to do, he says, is to take what an artist is about, what the theme of the show is about, and what the intended purpose is, and create a television production that allows these elements to come together.

A large production like the Tony Awards requires attention to every detail. But, says Smith, "the biggest concern is always time." Sometimes people ask him whether he worries that something unexpected might happen during a live show. "You want the production to be spontaneous," he tells them. "Sometimes you can set that up."

Carnegie Mellon alumni in the entertainment industry have a sense of camaraderie and connection, even if they aren't in the same class, Smith says. "I think we've all come away with a feeling of [having had] a wonderful theater education."

Carnegie Mellon alumni in the entertainment industry have a sense of camaraderie and connection, even if they aren't in the same class, Smith says. "I think we've all come away with a feeling of [having had] a wonderful theater education."

Carnegie Mellon School of Drama students, Noah Mitz, a junior, and Evan Purcell, a senior, interned at the 57th Annual Tony Awards. They worked under the show's lighting designer, Bob Dickinson, an instructor of lighting design at the School of Drama. Excerpts from interviews with the two students are below.

Carnegie Mellon School of Drama students, Noah Mitz, a junior, and Evan Purcell, a senior, interned at the 57th Annual Tony Awards. They worked under the show's lighting designer, Bob Dickinson, an instructor of lighting design at the School of Drama. Excerpts from interviews with the two students are below.

�

�